Grant and Susan in Peru

24 February 1998 - Arequipa, Peru

We're now in Arequipa, at 1 million inhabitants the second largest city in Peru. We headed off at mid-day on Saturday from Arica in Chile. Border formalities were fairly ordinary, though not quite as straightforward as the Argentina/Chile border. Got totally lost going through Tacna, then it was very hot riding until we gained some altitude. We were feeling pretty tired after a few hours so we stayed overnight in Moquegua in a nice hotel on a hill overlooking the town.

We're now in Arequipa, at 1 million inhabitants the second largest city in Peru. We headed off at mid-day on Saturday from Arica in Chile. Border formalities were fairly ordinary, though not quite as straightforward as the Argentina/Chile border. Got totally lost going through Tacna, then it was very hot riding until we gained some altitude. We were feeling pretty tired after a few hours so we stayed overnight in Moquegua in a nice hotel on a hill overlooking the town.

Sunday we drove into Arequipa, an easy ride of 200 km. It's always good to arrive in cities on a Sunday so as not to hit heavy traffic, but instead we arrived on a "Carnaval" day. The first thing we noticed as we drove through the city was the kids tossing water bombs at cars and shooting water pistols out of cars! Lucky for us they weren't targeting tourists on motorbikes, though we did have a couple of near misses! After getting thoroughly lost due to the absence of road signs, we ended up quite by accident a few blocks from the centre in front of a hotel which looked nice and new. Though it wasn't listed in the Handbook, we decided to check it out anyway, and ended up in a room with a private bath, satellite TV, safe parking for the bike and a nice courtyard for $30 a night. Definitely better value than in Argentina or Chile, where we paid $25 for a small room with a shared bathroom and no TV.

We've been wandering around Arequipa for a couple of days, now. It really does feel more like third world than it did further south, though it has also been very prosperous at some time in the past. Huge colonial buildings divided up into many little shops, each of which sells a great variety of things, but much the same as the shop next door.

As business consultants, we've also been bemused by the processes in some of the larger stores. For example, one medium sized store we were in sells bread, cheese & cooked meats, ice cream & juices. All the goods are safely behind counters staffed by different persons.

If you want bread, you tell the bread person what you want and she prints out a cash register ticket for you. If you want cheese, you tell the cheese/cooked meats person what you want, and she prints out another ticket for you. And so on. You then take all your tickets to the main cashier (and queue up, as this is the main bottleneck), who keys in the details of what you've requested into another cash register and tells you what the total is. You give her your money, she gives you back your slips stamped 'pagado' - Paid, as well as your overall receipt. Then you go back to the bread lady and give her all the slips, she keeps the bread slip marked 'pagado' and makes a check mark on your overall slip, and gives you your bread. Ditto for the cheese/meats lady, the ice cream lady, and the other departments.

This process has clearly been engineered, and the goal is maximum control! For these folks, a typical North American supermarket would be a major innovation, though we have seen at least one such smallish supermarket in town, so perhaps change is inevitable.

Another fascinating local process I observed is garbage collection. The fellow on the back of the truck has a large metal noise maker triangle which he uses to create lots of noise as the truck drives on its route. Why? The noise tells everyone to bring their garbage out and put it on the truck, assisted as necessary by the truck driver. So folks run out of their houses with their garbage and chase the truck down the street to get rid of it. I guess if you're unlucky enough to be out when the truck comes by you have to wait until next time. Talk about getting your customers to do the work! But it set me to thinking - perhaps most municipalities could have two systems - a 'basic' service such as I've just described which would be very cost-effective, and a 'deluxe' service where the garbage collectors actually pick up the bins from your yard but which would cost more. There seems to be another downside to the system though - many people just toss their garbage - including old furniture and car parts etc. - on the highways, causing incredible piles of garbage at the roadside.

We'll be here tomorrow I expect, as we've both gotten 'turista' to varying degrees, and are getting over it slowly. Not sure of the culprit, although we've started to treat the bottled water as being suspect enough to use water purification tablets in it. Reminds me of the Nairobi bottled water scandal when we were in Kenya, where they discovered that almost all the bottled water was just Nairobi tap water! And the bottled water here tastes terrible - either extremely strong mineral content, too much 'gaseosa', or just plain tastes bad.

28 February 1998 - Chincha Alta, Peru (200 km south of Lima)

Two stinking hot (38.5 Celsius in desert) days from Arequipa to here - 820 km. About 200 km left to Lima. Definitely not boring roads. What Grant describes as good motorcycle mountain roads, but don't make a mistake! Lots of crosses and small monuments by road - sometimes 5-6 in one spot, marking the place where someone made a mistake. Minor hazards included lots of sand and rocks on road, often with no warning. Major hazards where the road edge has collapsed into the sea in places, usually with warning signs, but not always. Lots of road crews out working - clearing the road, shoring up the sides, etc. They like the bike - waving at us and cheering as we drive by.

Many enduring images on this stretch (and lots of photos). Shortly out of Arequipa we encountered ash grey crescent-shaped sand dunes in the middle of reddish brown desert - clearly sand has come from a long way away. Per the guidebook these are 6-30 m across and 2-5 m high, and the dunes move about 15 m per year.

Between Arequipa and the coast is very hilly. Between the hills are lush green river valleys surrounded on all sides by barren desert rock - amazing contrasts.

Along the ocean - from left to right you see ocean, green cultivated fields, sand dunes, the highway, larger sand dunes, bare hills above. In one spot the ocean is a steep drop about 85 m below the road, then steep sand straight up above the road to a similar or higher height. The sand is held back by retaining walls, but is spilling over the walls into the roadway in numerous places. We've seen lots of waterfalls before, but this was the first time either of us have seen sand falls - 15 meters wide and about 10 meters high!

Major eyesore is that there's lots of garbage by the roadside - much worse than in Chile or Argentina, approaching Libyan levels - this is a real indictment, as we didn't believe anywhere could be as bad as Libya for garbage! This is also a road hazard - Peruvians throw trash out their car windows without even thinking about it. Someone in a car just ahead of us threw a pop bottle out their window and it landed in the middle of the road - luckily it was plastic and not glass!

Tourist attraction of the day was the Nazca Lines, which are best viewed from the air. Instead we climbed up the mirador (viewpoint) along the Panamerican Highway. Pre-Columbian graffiti on a grand scale (an archaeologist would be horrified by this description). The town itself (Nasca) definitely not worth a stopover.

Nazca Lines, Peru

We also saw the residual effects of flooding in Ica, including sand bags in front of houses, mud piles at the side of the road, and the highway itself covered in hardened mud.

Stayed overnight at Puerto Inka, literally the ancient Inca port for Cusco. Natural harbor, nice sea breezes, ruins not very impressive, though. Not much left except one - two foot high walls. Fell asleep to the sound of the surf, woke up at 2:30 a.m. to the sound of a mouse in the room (trying to get at food in plastic bags). Then spent hours worrying about Hanta Virus and whether mice transmit it as well as rats.

Tonight in Chincha Alta at a Peruvian "3 star" hotel. Has a swimming pool, restaurant and rooms designed so that even after it was lovely and cool outside it remained stinking hot inside all night long - actually started off sleeping under a wet towel. 31.5 Celsius inside the room at 10pm (that's four hours after sunset here, and it was lovely outside) and no fans available! There was a ceiling fan, one speed only (guess which one) which merely redistributed the hot air.

1 March 1998 - Chancay (100 km north of Lima)

"Let's take this road - it's going the wrong direction but maybe we can find someplace to turn around."

Well, Lima must have the record for our shortest stay in a major city - 5 hours, and that was about 3 hours more than desirable! The plan du jour was to try to book a flight to Cuzco for Sunday evening or Monday morning, then find a hotel near the airport where we could leave the bike for a few days, returning to Lima on Wednesday. Didn't exactly work out as planned.

Shortly after leaving Chincha Alta this morning we saw an Inca Kola truck overturned on the right hand side of the road with its load of bottles spilled all over the right lane, with lots of broken glass. As we eased past the truck, we saw two more badly smashed up small pickup trucks, one with a body hanging out of the driver's window (the scene was being filmed by someone with a videocamera), and another body just lying on the road very close to the passing traffic. The accident must have happened a couple of hours earlier as the road crews had cleared one lane for traffic, but the corpses were still there. This particular stretch of road was in a valley with good visibility in both directions, so possibly alcohol was a factor.

Roadside memorial, Peru

We also encountered numerous lunatic drivers today, and saw at least five accidents in total. In fact, just shortly after seeing the first accident, we noticed that the bus ahead of us had obviously taken no lessons from the carnage - he passed a truck on a blind curve and forced an oncoming car to slow way down to let him in. I think bus drivers in this part of the world are actually worse than car drivers - not sure why. Mind you, the car drivers are as bad as any we have seen anywhere - easily competitive with the drivers in Cairo, Bangkok and Mexico City. Turn signals, staying in your lane, driving on the right side of the road (cars drive in the curb lane on the wrong side) all seem to be curious concepts best ignored. Buses stop right on the road, not pulling off to the side because if they did they would never get back into the traffic again, so all the traffic backs up behind them, while everybody tries to squeeze into one lane to get by. We saw one large bus blocked by a small one pull over two lanes to the left, all the way into a left turn lane at an intersection, cutting off numerous cars, then all the way back to the right lane, then jamming on the brakes to let off a passenger - just in front of the bus he had gone around, who was then blocked himself. Horns are used at any time for no obvious reason, except when the light goes green, then everybody honks instantly.

The handbook says the road into Lima from 100 km south is 4 lane freeway. Well, yes it is, but 40 km out of Lima, with no explanation, we got detoured onto a truly terrible old two lane road with enormous potholes and gravel stretches. This went on for 20 madcap km - everybody passing everybody - until we saw the reason - cars are using all four lanes coming from the north! Apparently Sunday morning the two way 4 lane freeway becomes 4 lanes heading south OUT of Lima - if you're heading INTO Lima you're screwed. Numerous detours and bad choices later, with nerves frayed, we were almost to the centre of town and found the freeway again. Quote of the day from Grant: "Let's take this road - it's going the wrong direction but maybe we can find someplace to turn around." Of course, we were going the wrong direction at the time anyway!

We finally found the airport around 2:30 p.m. and began checking on flights to Cuzco. First bad news - the heavy rains have caused long flight delays. For example, the 10:30 a.m. flight to Cuzco still hadn't left at 2:30 p.m. Second bad news - problems with other transport modes due to weather have caused increased demand for flights. There were long lineups at the ticket counter, but we persevered to the front of the line. Yes, we could buy a ticket to Cuzco. No, we couldn't buy a ticket back from Cuzco to Lima - you have to buy that in Cuzco. She checked the computer - no seats on return flights before the Thursday 7:30 am flight earliest, only a few available then, and none for the rest of the day - then the same on Friday. The whole thing started to seem too hard - probably the inertia caused by lack of air-conditioning in the airport (we were both dripping sweat). By mutual consent we decided Machu Picchu is best seen some other time of year. Felt bad about it, but what the heck - we missed the Amazon too. At that point, we didn't even want to stay in Lima overnight, though if we had seen a hotel which looked halfways reasonable we would have taken it. We didn't - in fact, the area around the airport is a really slummy industrial area and didn't look like anywhere you wanted to stop over. So, we continued north on the Panamerican and ended up in Chancay, about 100 km north of Lima.

Rio Huarmey, 2 March 1998

Wherein we and the bike go for a swim...

From the State Department Advisory received in Chimbote:

"Travelers to Peru from February to June 1998 should be aware that severe weather, including heavy rains, floods, and mudslides caused by the El Nino current, is affecting land travel in some areas of the country, particularly along the coast...Road closures and bridge washouts can occur unexpectedly and may affect travel plans. Major highways, including the Pan American Highway both north and south of Lima, have at times been closed because of mudslides."

Well, we had obviously been too smug about our sensible choice of the Pan American Highway vs. Gregory's ordeal in the Amazon. Today we got our comeuppance. Most of the population of Peru lives in the river valleys or at the mouths of rivers on the coast. And those rivers are flooding from rains inland. We knew there had been flooding in a number of areas, but naively assumed it was mostly over a week ago. As we passed through vast expanses of desert the idea of flooded roads seemed impossible. But we had heard on the news that there is a new lake in Peru - called La Niña, for obvious reasons, which has been created by the diversion of flooding rivers into the desert.

Shortly before noon today we saw something we'd never seen before - large pools of water in the middle of sand dunes. In many areas the road has been recently covered by water and mud, but it has dried up and been scraped off. Then we came to a low stretch and water was actually on the road - not too deep, though, and we drove through without incident. But much worse was to come.

Flooded sands in the desert, northern Peru

Just south of Huarmey the River Huarmey flooded the Pan American Highway on Saturday, and the road was closed for 16 hours. Sunday things improved and they started reconstruction work. But Sunday night more rain fell and by the time we got there at mid-day Monday the water was 1 to 1.5 feet deep and flowing across the road at a good speed - like a river with no bridge across. If the road underneath had been still good pavement we'd have been all right. But parts of the underlying road have already collapsed and it was impossible to see where it was bad because the water was too deep. On the left side of the road it looked like a mini Niagara Falls as the water surged over the edge of the pavement.

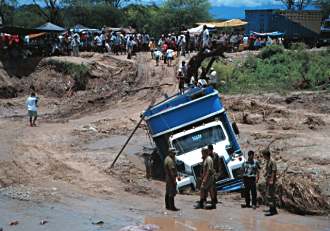

Bad news on the Pan-American Highway, Huarmey, Peru

Urged on by the local kids (and the impatient bus behind us), we headed into it with trepidation - well founded, as it turned out. Moments later we hit a bad stretch in the deepest, fastest flowing water and over we went. Oh, joy - drenched in muddy water, my favorite! The kids helped haul the bike up, Grant got back on but I elected to walk through the rest of the flood waters - almost 3/4 of a kilometer. He had a number of "assistants" to push him in case he got stuck - the assistance was more trouble than it was worth, as they were enthusiastic but clumsy. When I finally caught up with him back on dry land, he and the bike were not much the worse for wear - only a crack in the windshield and some gouges on the side of the saddle bag where it evidently hit some rocks or cracked pavement underwater. But we both looked like creatures the cat wouldn't drag in. We drove on into Huarmey and stopped for lunch at a tourist hotel. I'm surprised they let us into the place - my boots were full of muddy water and I squished when walking! We took our boots off in the parking lot and poured the water out before coming in to eat.

|

Waterfalls over the edge of the Pan-Am Highway, northern Peru |

Crowd round the bike after its unplanned bath, northern Peru |

Grant's story:

I pulled up at the side of the road to have a good luck at the scene ahead - dozens of locals running alongside the cars and trucks splashing through the rushing water, ready to help in case anyone got stuck, hoping for a 'propina' or tip. A couple at the side waved us to go ahead, indicating the depth of the water - one indicating mid-thigh, another pessimistic one indicating waist depth. The cop waved at me to go, a bus honked, but I waited until I had a better idea of what we were facing. We had many offers of help, as a dozen or so people crowded around us. Too many offers as it turned out.

Finally more or less ready, I pulled out into traffic, and stopped, blocking traffic behind and waiting to create a bit of space ahead, so I would have room to maneuver. A little speed helps a lot here, and the bike won't go as slow as the cars were going without stalling anyway. Pulling ahead, the locals running along with us and 'helping' by pushing in several directions at once, wherever they could get a hand on the bike. (the theory is a helping hand gets a tip). The going was easy, just a foot or so of water, but then we got into the deeper and faster water where the roadbed had been washed away, leaving large boulders and bouncing us around. Here the shoulder of the road had been washed away, leaving a four foot waterfall over the edge of the road a few feet to our left - and then we were over and in the water.

I struggled to my feet, standing on somebody's leg, and bent over to get at the bike, but there were too many helping hands in the way. I could hear, distantly through all the yelling and the roaring of the water, an electric starter cranking away, and the bike was lurching on its side towards the roaring waterfall. I looked down at the starter button, and there was a helpful hand firmly clamped around the handgrip and controls, pressing the starter button. A smart slap on the hand and it jerked away, stopping the mad rush to the edge, still a meter short. The bike was quickly hauled up, and I got back on. Susan elected to walk, and I headed off again. This time I realised what the problem really was - not the water, but the helping hands. Without Susan's weight on the bike, it was trying to float, but the helpers were pushing so hard that the back end was traveling sideways, threatening to catch up and pass me! I stopped and yelled at them to not touch the bike, and appointed a 'leader' to run ahead and show me the route through. Once again we headed off, this time much easier, in fact I almost ran over my leader, prompting him to spurt ahead. Reaching the edge of the water I pulled over amongst the watching crowd and stopped to wait for Susan.

Damage assessment - cracked windshield at the mounting points - some helper trying to pick up the bike by the plastic windshield, and a gouge and a couple of scratches on the right saddlebag. Also the bike was running on one cylinder, but a look into the floatbowls showed the right was half full of muddy water. Cleaned out, it ran fine. We donated a few pens and balloons to the crowd as well as a 20 soles tip to the two who were most useful on the run through the water.

After lunch and a bit of clean up we headed north again. One further small water crossing in the afternoon, and we stopped tonight at Chimbote, where we picked up a local paper with amazing pictures from the weekend's weather at Huarmey - we've kept it as a souvenir. Took us hours to wash out boots, socks, shirts, underwear, etc. etc. But all in all, unscathed compared to the poor folks who live in this country. We're a bit apprehensive about tomorrow - we know there's been flooding in Trujillo, and tonight we saw TV news footage of a washed out bridge in Chiclayo. Not sure whether that's the only bridge through. We'll try to learn what we can before leaving here, but at least the Pan American is the first road they work on.

Oh, well. Certainly not boring, and we got some good pics.

Trujillo, 4 March 1998

We have made it as far as Trujillo in the north of Peru but our rate of progress is slipping - we're down to 150 km a day. The Panamerican Highway is impassable north of here, so we tried an alternative route this afternoon - through Chiquitoyo on the coast. After several hours of terrible dirt and mud roads, and a number of easy water crossings, we encountered a stopper - knee to waist high, fast moving water on a dirt road for over 2 kilometers.

Bus on flooded Pan-Am Highway, northern Peru

As usual, there are always locals at the scene urging us to go through - indicating it's only a foot deep and just a short distance. Grant's theory is that they want to see you fall over, it's part of the day's entertainment and they then get to "help" you out for a propina (tip). He's become somewhat cynical about this after Huarmey, so he decided to walk ahead and check out the situation for himself. Two hours later, (that's how he knew it was over 2 km) he came back and declared it a no-go, but he had already paid a price - accidentally using himself as a depth gauge, he was soaked up to the waist. We headed back to Trujillo and found a nice hotel with a swimming pool and consumed gallons of cold drinks.

Trucks on flooded Pan-Am Highway, northern Peru

The newspaper headlines the next day proclaimed "Chiquitoyo totalment aislado!", which means this poor little town was cut off. Had we gotten through to the town we'd have been stuck anyway. Of course, for us it's just an inconvenience. But this phenomenon is making life hell for the people of Peru. Flooded homes are getting to be fairly common, and the destruction of bridges and large sections of roads also mean that food and other goods are not getting through to many communities. Clean water is becoming a scarce commodity, and we were asked by several folks if we had water to spare.

The road conditions we saw yesterday were truly stunning - as if an earthquake had torn the highway apart along the white centre line outside of Trujillo, large sections of highway collapsed and the remaining sections not looking too stable. Wouldn't want to be in a heavy truck on these roads now.

Pan-American Highway north of Trujillo, Peru, after El Nino

Sad news - this trip is ending for Susan here in Trujillo. I fly back to Lima, then on to Vancouver on the 11th of March. I have a day to get my work clothes out of storage and have a medical check up, and start work full time on the 16th. I should mention that I made the commitment to a mid-March start date at the end of January when it looked like we could easily get through to Colombia by then. Until very recently, we were still trying, but the road conditions have now made that impossible, and the project won't wait.

I have definite mixed emotions about it, but must admit I'm looking forward to clean water, and being able to eat salads, fruits and dairy products without worrying about them. Peru is a much harder country than Argentina or Chile, or even southern Africa.

Grant will continue north through Ecuador to Colombia at a leisurely pace. He can wait until the rivers recede and the roads dry out enough to cross. And in some cases, for the bridge to be rebuilt! He won't admit to it, but I think he was looking forward to being on his own for awhile - 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for almost two years is a lot of togetherness!

As fates would have it, though, Max Elia (Italian motorcyclist who we first encountered in Ushuaia) caught up with us today. Soroche (altitude sickness) kept him from continuing into Bolivia, so he has been on the same road a few days behind us through Peru. He only made it 200 km. (but at 5000m altitude) into Bolivia before getting so sick from the altitude he was throwing up and couldn't see to drive and had to stop. So, he and Grant will travel together at least for awhile - they can help push each other's bikes out of the mud!

Grant:

How's this for coincidences: Twice now (three times if you include the first meeting) we have been walking down a street and there's Max. Twice he was on his bike and this time on foot. In all the places and possible moments we could so easily have missed - and we were both in Arequipa at the same time and did miss - it's pretty amazing that we would meet like that. This time he was on his way to the same Internet Cafe we had just left.

We will do a little sightseeing in the area while we wait for Susan's planned departure date and get everything reorganised for travelling solo. I plan to travel considerably lighter than in the past with Susan, especially with the road conditions in mind.

The adventure continues for one of us, at least!

9 March 1998 - Trujillo, Peru

Susan:

Grant and Max left this morning. They have had at least 2 days of dry weather here on the coast, though that doesn't mean there hasn't been rain in the mountains where the rivers originate. The bad news is there's little breeze, and it was already stinking hot by the time they left at 9:30.

Last night we discovered that the leather pants had been hanging up in the closet for several days but were not completely dry from the recent river adventures. Bad news bears! The mold was truly disgusting, and Grant's were worse than mine because he had got more of a soaking the following day. So, they had to be completely washed again, and leather takes a long time to dry. Grant's were still slightly damp this morning by the time he left. Yuck! I am NOT consumed with envy at this point.

We've divided stuff between what I'm taking back to Canada and what Grant's keeping. I made sure he had the South American Handbook, vitamins and water purification tablets, plus a few cans of tuna so he doesn't starve. He's also keeping my Canon and the print film and will shoot both slides and prints going north.

Max had picked up another motorcyclist Friday afternoon and brought him back to our hotel. Aviv Rabinovich (Israeli, in case you didn't guess) had just come through from the north with a Japanese motorcyclist (who we didn't meet), so he regaled us with stories about the horrific road conditions ahead in the far north of Peru and Ecuador - mud being the most common condition, flooded roads being the next most common condition.

Grant and Max took it all in, Max looking less cheery than his usual ebullient self at the end of it. Grant is feeling pretty optimistic about the bike handling now that he has about 200 pounds less weight (me and my stuff and a sleeping bag and the computer - leathers are pretty heavy), but Max is not very experienced on bad roads. He only started riding a few months before he left for South America, and up to now the worst he's encountered is bad gravel roads, not mud! All part of the adventure, eh? At least he's with a pro.

We've set Grant up with an e-mail account on Hotmail since I'm taking the laptop back to Canada for work. So, he will continue to report when he is able to get Internet access as he heads north to Ecuador and Colombia.

Tuesday, March 10, 1998 - Grant and Max continue to Ecuador

Grant:

Aviv Rabinovich had just come through from the north on a KLR650 Kawasaki, and gave us a less than encouraging report. He looked at our bikes, especially my street - Metzeler Marathon ME88 - rear tire, and said "You won't make it on that." Gee, just what I needed to hear. And nothing available here that would even come close to big enough. My front was a 300-21 Bridgestone Trail Wing, semi-knobby, but well and truly worn, especially on the left side. Too many thousands of kays leaned over to the left against the wind, all the way down Argentina then most of the way up Chile as well. That row of knobs was just about gone, and the rest wasn't any great shakes either. Best replacement for that was a US$17.00 2.75-21 "Made in China" Cheng Shin knobby. Perfect for the local 175cc trail bikes, but a little - well, a lot small for the Beemerbago. I guess I made it this far on what I have, I can make it a little farther, just have to ride a little smarter.

Max and I finally set off from Trujillo, leaving Susan waving sadly (well, maybe not so sadly, she had a pretty good idea what was ahead of us) goodbye behind us and headed off for fun and adventure with the already notorious El Niño. We arrived at the spot where Susan and I had been turned back a few days before to find that trucks were still not getting through, but people and some cargo was. I left Max with the bikes and joined the throng walking the 100 meters over rough, broken ground to the crossing point a little way down river.

A one-meter wide bridge of 5-inch pipe had been hastily thrown down over the river and lashed together with rope, then topped with logs and miscellaneous bits of wood. Safety consisted of a hand rope along one edge. Men were staggering over with huge sacks of rice and flour and everything else you could imagine, along with a steady stream of humanity, chickens, goats and pigs. As seems usual, everybody was in a hurry for us to cross, waving us on and eager to help, "no hay problema para moto" was the watch cry for all. Right, all we had to do was lift 300kg bikes up a half meter onto the top of the bridge, which they were all insisting was the only way and of course they would be glad to help...

I waved them off, and had a good hard look at the problem. It was possible, with care, to pull out a post supporting the safety rope and push it aside, and ride right at the edge of the bridge, keeping the wheels in the last groove between the outermost downstream pipe and the one next to it, five inches from the rushing floodwaters. No safety rope anymore of course, but I didn't think it would do us a lot of good anyway.

I walked back to the bikes, and said, "Let's do it!"

I led the way, bouncing and wobbling over the half-meter deep ruts to the bridge, the usual helpers tagging along. I stopped and looked back, and there was Max... falling over. We got him back up and parked, and then, after much explaining and yelling, got the post pulled at the other end.

I rode up and put the front wheel on the bridge, and braced for the hard part - a piece of pipe sticking into the path. I would have to lean the bike well over to the left, over the rushing river and away from the bridge and safety in order for the cylinder to clear the pipe. With a helper behind holding on, and another on the bridge, I put one foot on the bridge and the other on the left footpeg...and leaned the bike over as far as I could, not enough, a deep breath, then over some more - there was a shout - ok! - and I fed the clutch and throttle, and moved carefully forward, bumping the pipe and joggling the bike, then I was past. I stopped for a quick "photo opp", then straight for 15 meters, keeping a perfectly straight line in the groove, past the rope and post held back out of the way, a bump off the end, and I was over. Roars of approval, "ole!", and a deep sigh of relief from me.

Max was next. He had a little more trouble getting onto the bridge, but once on didn't have to lean over so far, as his bike had a little more height at the cylinders than mine. Soon he was over, and it was time to pay off the helpers. Everybody tried to crowd in on us, "me me me me!!!" I paid off the ones I recognized as having helped, but ran into trouble on the last two. I only had one bill left, and two people to pay! I indicated that they should split it and gave it to one. Wrong move. He split, and the other one followed us out to the road, wailing that he didn't get anything. As he had actually been one of the more useful ones I stopped and dug into my pocket for some coin and paid him too.

Max had tied his helmet onto the back of his top box, and as he was crossing the bridge it had fallen off the top and was hanging down behind. It was hot, and we were sweating bullets, so he left it there while we raced away from the madding crowd and any more possible helpers crying poor. A few kilometers down the road, there was a wide river pouring over the road, about a half a kay wide, but it looked easy, not too deep although fast, so we just zipped across. No problem - but Max's helmet proved a perfect bucket for the spray off the rear wheel! Yeccchhh. I had a pretty good laugh at his expense.

He decided to leave it there until we could find a clean water source to rinse off the mud. We did, but we found another water crossing and a dirt road detour first!

We stopped along the way for a break, and I dug into my gorp (good old reliable peanuts and...whatever there is) and dug my hand in for a fistful, and found that Susan had arranged a treat for me. She had added chocolate somethings to the gorp. I say somethings because they had melted in the heat and I now had a sticky, gooey mass of chocolate and nuts. All over my hand. Yeccchhh again. The only way to eat it was by dipping my tongue in and licking. Max's turn for a laugh.

We managed 250 km. that day, and stayed at the Hotel Pelegrino, a dumpy little place in a dumpy little town. Cheap at 14 sols, about US$4.00. Later that evening, I dug into the gorp again, and discovered that the ants liked the chocolate too. It was crawling with them, hundreds of them all over and in both bags of it, right through the ziploc bag plastic, and fast disappearing down the wall and into a hole. Shit! They bite too!! I was hopping madly around trying to get the bags away from the rest of my gear, knock the ants off everything, then more importantly me as I got bit, and punctuated by furious swearing every time I got bit - which was often - all to the tune of Max's laughter. So much for the gorp supply.

In the morning, it was my turn to laugh. Max had brought in his top box, which is where he keeps his food - including the honey and chocolate. Oooops. The honey was in a cheap plastic container which had popped open from the bouncing over terrible roads, and worse detours, and was smeared over... everything. The ants were too. Millions of them. It took an hour to wash out the box, trash all the food and clean the muck off. Another auspicious, early start.

Yet another river crossing, northern Peru

By 50 km. out of town, I had lost track of the number of river crossings and bridges washed away, despite starting off by counting, plus sand and mud on the road, slides covering the whole road etc. We arrived in Piura very ready for lunch, and slopped through the maze of muddy, garbage strewn streets looking for somewhere to eat that looked safe, as everything looked truly grim and disgusting. And then there was Domino's Pizza. Truly an oasis in a sea of filth and muck. Good pizza too, just like - well almost - the real thing.

Worn out after 201 km of constant bad road, we pulled into Sullana for the night shortly before dark. Last stop before Ecuador.

We confirmed that the coast road, the good road, the new road, through Tumbes was absolutely closed and impassable, and would be for some time. The other route through Macara and Loja to Cuenca was old and in poor repair, with lots of problems, but was apparently open. Okay, I guess that's the way we go.

Wednesday, March 11, 1998

After much futzing around in Sullana trying to find the post office for Max, then chasing all over town looking for bottled water, we finally got out of town at noon.

Grant and bike leaving hotel in Sullana, Peru

Everybody was very helpful, but none of them had a clue where the post office was. We were directed to several different places, all wrong, before we finally find it hiding in a grotty old building with a small sign, very high up, and around the corner from the entrance. We then asked somebody where we could find "Agua Pura" and he said he would show us the way. Great, thanks. Driving all the way through town - again - he pointed to the sign for "Piura" proudly and waved goodbye. No, we really don't want to go back to Piura, Peru, been there, done that. Try again. Everybody really WANTS to help, and does, even if the information is dead wrong and useless. I think they hope that someone along the way will know the real answer.

After one small easy river crossing we hit a biggie just out of Sullana. The bridge was washed out, and we could tell that the ford was a big problem. First, the large truck buried in the mud up to the hood, just the cab windows and the upper part of the box sticking out, and then the large farm tractor towing another truck out of the river. There were two approaches, one steeper than the other. The best approach was down a steep 30 odd degree bank, or about 6-8 meters of mud, into the river, deep and fast (of course) then fairly flat on the exit from the river but then another steep bank up the other side. As usual, just getting to the river was messy, through the mud and slop of a farmer's field. We watched a couple of trucks go through, then I said, oh what the hell. Let's go, I think if we go there and keep the speed up we'll be ok. Max felt brave, and charged through first, down the ... shit, wrong approach, the hard one. He made it through in a huge splash and spray of water and steam, and pulled up on the other side.

Truck stuck in mud, northern Peru

So much for the hard route, I was now forced into it as a truck had just gotten stuck on the easy route. Splash! Water pouring up over my knees, up the windshield and everywhere, bike slows, more throttle, a gasp and we're through. Bike stalls on the other side, not idling anymore. Water in the carbs. I pulled off the float bowls and poured out the water. Easy.

Next problem though is getting up the embankment to get out of here. The usual mass of people everywhere, in the path and at the sides, blocking the way. Max, in the lead, honks and screams at people to get out of the way, and then heads on up. A little too soon, it's not quite clear, one man struggling up with an enormous sack over his shoulder, steps right into his path. Stuck in the muddy rut, Max has nowhere to go, can't hold it, and falls over into the slop. We pick him up, and with a couple of helpers push him to the top, spraying mud everywhere from the spinning rear tire.

I followed, then we fought our way through the usual chaos at these places. People are going in both directions of course, and everybody is absolutely going to get there first, therefore they take advantage of every possible inch they can, in both directions, on a one to one and a half lane road. Result is total gridlock, screaming and yelling and constant honking as drivers try to force their trucks through first. A lot of zigging and zagging through the tiny gaps, taking turns blocking traffic for the other, we made it through.

Truck stuck in mud, northern Peru.

Another detour, and another washed out bridge. This time I think we were on the wrong road, but it was a long way back to the previous intersection, and it did look possible, although very dramatic. A tricky trials ride down about ten meters to the river, through and up another ten meter slope on a narrow sandy path. I went first and had no problem, which gave Max perhaps a little too much confidence. Coming up the other side, he didn't have enough speed up, and had to gas it hard coming up - heading sideways, climbing the edge of the path, back wheel spinning, front wheel lifting, for a moment I though he was done for. But he made it once again, a big proud grin plastered on his face.

Thirty km. or so of trail and narrow, rocky dirt road, wandering through small villages, past fields and cows, scattering chickens as we went, we made it back to the highway. From there, the Peru / Ecuador border was an easy run on a wonderful new highway, with only the occasional small washout or mudslide, and the usual rocks on the road.

Sometimes you can't tell if the rocks have fallen or were left by truck drivers. In what I will call the third world for lack of a better description, the trucks are somewhere between tired and trash, usually closer to trash. As a result, they often break down at inconvenient times, and since the brakes, especially the parking brakes aren't worth much, the procedure is to hop out - quickly - and put a big rock or three behind the wheels to hold the truck on the hill. The safest thing for the truck driver when he leaves is to just drive away. Leaving the rocks where they were - in the road. Right on the tire track. You see them all the time, scattered about on the road, right on the line, wherever there are hills.

We were clearly leaving civilization behind as we headed up into the mountains. More and more of the houses were made of sticks and mud, with grass thatch roofs, dirt floors sometimes visible, and the forest encroaching closely on the villages. The villages were also becoming rarer as we headed away from the coast. We stopped for lunch at a small restaurant just at the Peruvian side of the border, not knowing how long the border formalities would take. The restaurant consisted of a small adobe building that was the kitchen, a plastic tarp slung over a couple of poles for an awning, dirt floor, all perched on a steep hillside above the road. We talked to some truckers and local workers eating there. The big crop of the moment was limes, tightly stuffed into 70 kg sacks, which the workers lifted off small local pickups, slung over one shoulder and loaded onto bigger transport trucks right there. A large truckload of limes could be bought right there for about US $70.00. A good seasons crop for some of these small farmers.

See Ecuador for continuation ...

Member login

Announcements

Thinking about traveling? Not sure about the whole thing? Watch the HU Achievable Dream Video Trailers and then get ALL the information you need to get inspired and learn how to travel anywhere in the world!

Have YOU ever wondered who has ridden around the world? We did too - and now here's the list of Circumnavigators!

Check it out now, and add your information if we didn't find you.

Are you an Overland Adventure Traveller?

Does the smell of spices wafting through the air make you think of Zanzibar, a cacophony of honking horns is Cairo, or a swirl of brilliantly patterned clothing Guatemala? Then this is the site for you!

Hosted by Grant and Susan Johnson, RTW 1987-1998

Johnson's Home

Who Are We?

The BIKE Story

Press Stories about us

Our "Rules of the Road"

Photo Album 500+ images

"Quick" highlights -

Top 31 photos

Mexico

Central America

New Zealand

Australia

Europe

England

Isle

of Man

Norway

Sweden

Denmark

Germany

Netherlands

Spain

Gibraltar

Africa

Tunisia

Libya

Egypt

Kenya

Tanzania

Malawi

Zimbabwe

Botswana

Namibia

Caprivi Strip

Etosha

Sossusvlei

South

Africa

South America

Argentina

Tierra del Fuego

Chile

Peru

Ecuador

Colombia

Next HU Events

Be sure to join us for this huge milestone!

ALL Dates subject to change.

2025 Confirmed Events:

Virginia: April 24-27

Queensland is back! May 2-5

Germany Summer: May 29-June 1

Ecuador June 13-15

Bulgaria Mini: June 27-29

CanWest: July 10-13

Switzerland: Aug 14-17

Romania: Aug 22-24

Austria: Sept. 11-14

California: September 18-21

France: September 19-21

New York: October 9-12 ![]()

Germany Autumn: Oct 30-Nov 2

2026 Confirmed Dates:

(get your holidays booked!)

Virginia: April 23-26

Queensland: May 1-4

CanWest: July 9-12

Add yourself to the Updates List for each event!

Questions about an event? Ask here

Books

All the best travel books and videos listed and often reviewed on HU's famous Books page. Check it out and get great travel books from all over the world.

NOTE: As an Amazon Affiliate we earn from qualifying purchases - thanks for your help supporting HU when you start from an HU Amazon link!