42Likes 42Likes

|

|

1 Aug 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2010

Location: Santa Cruz, California

Posts: 316

|

|

|

The Stans Without a Plan - Part II

The following morning brought a continuation of cliff side riding with epic vistas and creek bashing.

The road eventually turned into a smooth two track that we could just flow along in second gear, crisscrossing the turquoise stream periodically and railing through a turn here and there. There was no other traffic at all other than two cyclists that we saw going the other direction. Even with our broken spring, it was a super fun road to ride – pretty much the perfect sort of terrain for a dual-sport bike. We found an epic camp spot for the night in a patch of lush grass right beside a crystal clear stream. By the time we’d made camp, a light rain had started, but Mike and I stood outside anyway, cooking dinner and drinking whiskey. This was what we'd come for.

The next morning, the two-track riding continued and the spot of rain had swelled the mud puddles somewhat. While I took the easy option around, Mike opted for a glorious blaze through the puddle. I should mention that two days prior he did manage a solid wheelie on the Tenere, fully loaded with Rebecca on the back when he rolled on the throttle to escape a pursuing dog. So such a blast through a puddle should be no problem, really.

There were no rocks below the surface, only slippy mud that sent Mike spinning and then down. The whole village turned out to see the subsequent yard sale once we extracted the bike from the brown water. As always, they were very friendly and we felt bad turning down their invitation to stay in the village for the night. This soggy business was all good practice, as we knew that a difficult creek crossing was coming up.

It wasn’t so much as the depth of the water or swiftness of the flow that provided the difficulty, but the huge cobbles that made up the stream bed, perhaps half a meter in diameter on average. My ride across was about the least graceful feat on a motorbike you could imagine, which convinced Mike to walk the Tenere across. We’d both made it safely across without another dunking and we were stoked. The cows on the far bank gave no acknowledgement of congratulations whatsoever.

We found a spot for lunch and Mike put the Tenere down for an afternoon nap.

We rode through a few smaller creeks en-route to rejoin the Pamir Highway. There was still no tarmac, but the rocky road we ascended was now graded. Both our bikes had been running like total crap due to the altitude, which generally stayed above 3000m (about 10,000 ft). We also hadn’t cleaned our air filters since we’d spent hours eating truck dust riding away from Dushanbe.

At the next steep ascent, which began above 3800m (12,500 ft), the Tenere killed and wouldn’t restart. We found that the plugs were carboned up like the inside of a chimney from running rich at such high altitude and the air filter was caked through with dust, so we were pretty hopeful we’d be able to get the problem sorted out. Sure enough, when we cleaned the plugs and the air filter the bike started right up. Hoorah Tenere! She didn’t make it very far though before she killed again. We feared that another electrical gremlin might have crawled into the Tenere. It seemed as though the normal stuff we’d done had gotten the bike going again. Could it just be that she’d reached her altitude limit for the way the carburetor was set up?

We were running out of things to try and we were in the middle of the mountains on a ‘highway’ that we’d seen only 1 truck pass in three hours. The closure at Khorog meant that there there was very little traffic coming our way and the clock was ticking -we only had two days left on our Tajik visas. Team Tenere had already endured an odyssey to continue the journey from Kazakhstan and we were resolved that it wouldn’t end here, but first we had to find a way somewhere else.

|

11 Aug 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2010

Location: Santa Cruz, California

Posts: 316

|

|

|

The Stans Without a Plan - Part III

Dyna Rae was sputtering and coughing as we climbed into the stratosphere of Tajikistan and despite our efforts, the Tenere still wouldn't start. Our fading hope was that the blue beast was just suffering her own bout of altitude sickness.

The only place worse to be stuck with a bike that wouldn’t run would have been where we had just come from or where we were about to go. We’d descended from the muddy, creek bisecting, high mountain track to reach the gravelly stability of the Pamir Highway. The trouble was that there was absolutely nothing but mountain wilderness between us and the next town, called Murghab, a 5 hour ride north. Fortunately, there was some kind of outpost nearby with a family living there who let us know that there would be a mini bus coming by that night which could carry Mike and Rebecca to Murghab.

Jamie and I rode off leaving Mike and Rebecca behind, hoping to make Murghab before dark, but we weren’t even close. Within an hour, a storm rolled in and landed on us like a hammer. I was optimistic that we’d outrun it, but it was soon clear that idea was pure folly. Now we were splashing through one track of a deep two track and I could barely see where I was going. I had my visor up to see better, squinting through the million pinpricks of raindrops on my face. The clouds were so dark and thick that it seemed the sun must have already set, but it was still back there somewhere. We should have made camp while we had the chance, now there was nothing but steep slopes of loose scree on either side of the road and the storm only seemed to be gaining intensity. As we rode on I gritted my teeth and cursed my poor judgment that had put us in this spot. There was nothing to do now but continue riding through this high mountain maelstrom and try to stay upright. Finally, after another hour the storm found a break and a flat spot appeared at the roadside. I pulled off the road and exhaled for the first time in an hour.

The Tenere’s symptoms had been disturbingly similar to a failure of the CDI unit that we’d already replaced in Dushanbe. From Murghab, Mike got onto the internet and found that the same shop in Osh, Kyrgyzstan that had found a spring to fit the DR650, may also be able to either replace or repair the Tenere’s CDI unit. Stoked! We just had to get the bike to Osh.

Did you know that you can fit a Yamaha Tenere in the back of a Mitsubishi SUV? We didn’t either. It turns out that with enough convincing man grunting, she’ll slide right in.

After receiving a bit advice about the roads from some friendly Polish motorcyclists coming from the other direction, Jamie and I hit the road for Osh, once again chasing down team Tenere that sped ahead of us.

The ride into Kyrgyzstan was pretty astonishing, crossing 4 high mountain passes and rounding the shores of crystal alpine lakes.

The highest pass was 4,559m (15,285 ft), which I think is the highest we’d ever ridden. While she runs terrible at high speed up at this altitude, she never looses torque at the low end, and since the road was really rough, she rode just fine.

There were a few more creek crossings to negotiate on the way up to the border. They turned out to be pretty easy, but it was hard to tell by looking at them, so Jamie jumped off and hop-scotched to the other side, just to be safe.

There is a 20km section of no-mans land between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, with a terrible road connecting either side. It’s one of the longest gaps like this I’ve ever been through. Diplomatic relations between the US and Kyrgyzstan must be fantastic, because it was among the easiest border crossings we’ve ever done. No visa needed, no questions asked, just a hearty ‘Welcome to Kyrgyzstan!’ and we were off again.

We didn’t make it far past the border before it was time to find a camp, and Kyrgyzstan didn’t disappoint. We turned off the road onto a track that wound into the hills past widely spaced yurts with flanked by the herders’ flocks of cows, horses, sheep, and goats. This place is like sheep heaven. The Kyrgyz people traditionally lived as nomadic herders, completely outside of cities until the mid-ninetieth century when the Soviet Union came into the picture and collectivism helped to create larger villages and cities. Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, some have returned to nomadic life and others practice it during the summer months. It feels fantastic up here surrounded by this landscape and the animals, looking over the plain spotted with yurts.

Riding towards a snowy mountain peak, we turned off the track to ride cross-country straight up the grassy hills. The grass was trimmed short by the furry munchers and the ground was solid, so we didn’t really need a track at all. It was like a dream rolling up and down those hills. Once we were far above the yurt settlements, we found a shallow depression in the hills that gave us some privacy from all directions but still provided a clear view of the mountain. The grass felt nice on our feet and the air was cool. It was one of the most epic campsites we’ve had the whole trip.

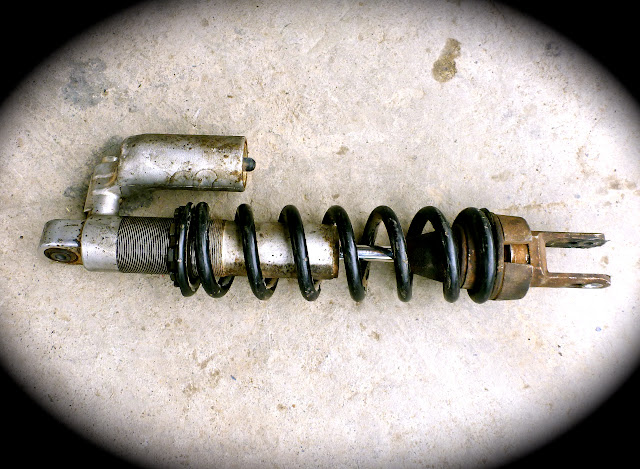

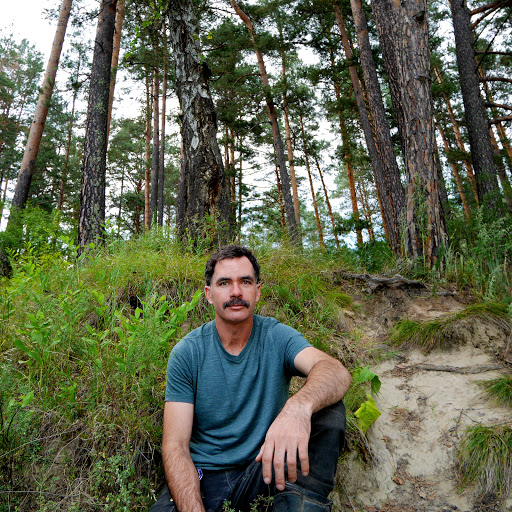

In the morning we the bounced down from our grassy mountain nest and headed into Osh, where Mike and Rebecca were already waiting for us. Mike and I set off for the MuzToo workshop owned by a Swiss guy called Patrick. MuzToo is exactly the kind of place that travelers like us hope to find on the road. He let’s travelers work on their own bikes at the shop and use the tools, and if you need help he’s a great mechanic himself and mechanic work from his workers comes at a reasonable cost. He managed to find a spring that would fit our DR650 and measured it against a DR650 that he had stored there to make sure it would fit. He also has the most Yamaha XT’s I’ve ever seen in one place – about 35 in total that he uses for his tour company.

I tore into Dyna Rae to extract her noisy, broken shock spring. It’s not too much trouble on the DR, just take out the air box and the shock mounting bolts can be removed. I soon had the beautiful new shock spring, with a slightly heavier spring rate than our current one slid on to the shock and she was about good to go. I was so stoked - after more than a thousand miles with a broken spring through Central Asia and the Pamirs we would finally have a fully functional shock again and Jamie would be getting launched skyward a bit less often. If not for Patrick, we may have been nursing the bike all the way to Vladivostok. If you need help with a bike in Central Asia he's the man to find.

The guys at the shop got out the multi-meter and confirmed that the Tenere’s problem was indeed the CDI unit. The replacement that Mike bought was used and perhaps didn’t have much life left in it. Unfortunately, this CDI unit was injected with rubber, making it irreparable, and plugging in spare CDI’s from one of the XT’s didn’t work either. Removal of the stator cover revealed that the Tenere’s stator had a couple design differences that meant the CDI units weren’t interchangeable between bikes. Given Mike’s schedule, it would take too long to get another CDI bought and shipped from Europe, meaning that this was the end of the road for Team Tenere. Mike sold the bike to Patrick for slightly less than he had bought it for and that was that.

Mike and Rebecca had gone through so much to make it this far and we were all bummed to have the journey cut short when the Tenere decided she was ready to call it quits.

Mike would fly to Ulaanbaatar from Osh, and Rebecca planned to head back the way we came, running the high altitude section of the Pamirs between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. She needed a way to carry her stuff, and at the time of our departure idea at the top of the list was to buy a spirited donkey at the Osh animal market. I really hope that happens. A lot.

Patrick pointed us towards the best tracks to ride in Kyrgyzstan and Jamie and I headed off north back into the mountains. The roads were very slow going in second gear and we made a wrong turn onto a road that was still being built, which required some backtracking. We were headed to a lake called Song Kul, winding high up into the mountains once again where the air got nice and cool and the landscape looked like paintings on a wall.

At Song Kul we found a symphony of clouds in action, colliding above the lake. We made camp on a grassy plain absolutely filled with cow pies. It looks pretty, but we were literally camping in a sea of manure. The storm that built during the afternoon raged all through the night and we were happy to be snuggled up dry inside of our tent.

The lake basin was vast – much larger than the lake itself and absolutely filled with lush grass. You could probably fit ten times the number of families’ yurts and flocks of animals in this place and they would still barely be able to see one another. Riding out in the morning, the rain was light but persistent as we reached the basin edge to descend a muddy, rutted track back down to lower elevation.

In the capital city of Bishkek, we met up with our friend Mahsa and her riding companion, Charlie. We’d last seen Mahsa in Addis Abbaba, Ethiopia. She’d come a long way since then, riding her Yamaha XT through Oman, Saudi Arabia, Iran and the Stans and was now on her way back home to Spain. But I think she’ll soon be dreaming up the next adventure.

Jamie and I had a long way to ride across Kazakhstan – nearly a thousand miles, so we reluctantly left the comforts of Bishkek behind and got moving again. We wild camped our way across Kazakhstan, finally outrunning the heat after three days of riding. One night camping near a necropolis, we were visited by a pack of wild horses that came right over to have a look at us. Jamie tried to communicate with her best horse whinny and I swear she got a response. As dusk fell, when we should have been making dinner, we just kept staring at the horse antics. Wild horses. Couldn’t drag us away.

Mike flew back to California two days ago and is already back at work. By now, Rebecca should be just about geared up for her traverse of the mountains back into Tajikistan, this time on foot. Her donkey ownership status is currently undetermined.

We’re certainly going to miss having Mike and Rebecca on our wing for the upcoming journey through Mongolia. Between luggage debacles, bike breakdowns, and detainment by a tyrannical regime, they’ve had a full-on adventure the last few months. It couldn’t have been easy to maintain a positive outlook while enduring this little odyssey, but that was what they did. Mike has however threatened multiple times that next year he’s going on a cruise. Via con Dios Team Tenere.

|

18 Aug 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Sep 2007

Location: Lutterworth,Midlands, UK

Posts: 573

|

|

|

as always great photos of an epic adventure.

bad luck with the tenere

|

21 Aug 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2013

Posts: 679

|

|

|

Thanks for the update, that's some trip you're on. Central Asia looks absolutely immense. Definitely next on my list!!!

|

26 Aug 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2010

Location: Santa Cruz, California

Posts: 316

|

|

|

Making Tracks across Mongolia

Making Tracks across Mongolia

Looking at the map, it seems that we’re about as far from an ocean as we could possibly be anywhere on the planet, about 500 miles northeast of the Mongolian border in Barnaul, Russia. It must be more than 2000 miles in any direction to find an ocean coastline. The Stans had turned out to be kind of a bigger deal than we thought with searing deserts, landslides, flooding, and broken bikes. I suppose it’s silly to presume to judge what any place holds just by examining the outlines of its borders, but they just didn’t look that big on the map! We’ve got a hell of a long way to go to the other side of Asia and summer is fading fast. Winter is coming.

Barnaul is our waypoint en route to Mongolia where I had a set of tires shipped to replace our badly worn set that have been on the bike since Croatia, more than 14 thousand miles back. We rode off from Barnaul without a clue what we’re headed into, just because we had tired of looking stuff up and figuring out where to go. We headed into Russia’s Altai Mountains on some brand new knobby rubber. Our plan was to simply blast to the Mongolian border as quickly as possible, but as we rode, the landscape turned lush and beautiful as the road wound along a river. We kept seeing awesome camp spots by the riverside and finally just had to stop to make one of them our home for the night.

Jamie made friends with the tiny locals.

I got woodsy.

The rain dumped on us all night, finally abated in the morning long enough to pack up and get riding, but not for long. The Altai is a beautiful place if you don’t mind enjoying the views a bit soggy.

We mostly camped in cow pastures and have gotten rather used to being surrounded by cow patties.

The cows played coy at first, but in the end kept creeping up on Jamie. We think they were planning something nefarious. Sneaky little buggers.

After spending several days more than expected in the Altai, we finally motored up to the Mongolian border, where we found our cage driving counterparts in line. The Mongol rally participants racing from London in the crappiest cars they could duct tape together were already kicking up the dust in front of us, ready to tackle Mongolia’s tracks in comically inappropriate vehicles.

Jamie got down with some maps to figure out the best way across a thousand miles of the wild Mongolian steppe. We forgot to bring a map. They laughed at us. We took photos of theirs instead. Problem solved.

Unfortunately we’d arrived to the border at about lunch time, which turned out to be a fairly drawn out affair. It was pretty annoying since we only needed one more stamp to get moving. We were less annoyed when we looked outside the office and saw that it was snowing, and no longer felt like riding anywhere. This didn’t bode well for our crossing of Mongolia along the northern route that had lots of creeks that could swell to flow levels that made them uncrossable on a bike.

At the border, we’d met up with a Swiss rider called Jonathan on a KLR who we’d first met in Kazakhstan. The three of us rode together; taking a detour to bypass the biggest river crossings that we’d heard had caused two riders to turn back the day before. At every meadowy stop, the local band of horses seemed to find us and come over for a look.

The Mongolians are virtually born on horseback and can just about ride before they can walk. They ride everywhere and seem more comfortable in a saddle than standing on the ground. We eventually learned that the bands of horses we found roaming around everywhere always belong to someone, and have been trained for riders. They are allowed to roam the grasslands freely until needed by an owner. They aren’t really wild, but they seem to lead a pretty close-to-wild existence out here on the steppe that’s wonderful to see. Back home I never really understood some people’s fascination with these creatures, but after so much time watching them in Mongolia I now do.

Outside of a few hundred kilometers of Tarmac, mostly laid down on the approach to the capital city, Mongolia doesn’t really do the road thing. They’re into tracks. Lots of tracks. The dirt tracks spill down hillsides and snake off into the valley as far as we could see. The pale green canvas is framed by low mountains and is only occasionally marked by the herder’s white gers, what we would call yurts, and their continuously munching livestock. The vastness of it all just fills your lungs with air and lightens heavy thoughts. A journey through this landscape can’t help but feel epic in scale.

We rode with Jonathan all day, traversing north from the town of Elgii towards the northern route and the town of Ulaangom. He rode faster than us and was soon out of sight. The route is often a dozen tracks wide and we couldn’t possibly always select the same one. Usually they converge with one another, but sometimes they don’t. At some stage we lost each other and we never saw him again. We had a long break on a hillside above a lake, so we figured he couldn’t still be behind us and rode on figuring that we’d eventually find him in Ulaangom, but he wasn’t there either.

We hoped everything had gone OK for Jonathan, but by noon the next day it was time for us to ride on. There were a few creek crossings and mud pits created from the rain of the past few days, but it was usually possible to find a way around any obstacle through the grass.

I’ve never ridden anywhere like Mongolia. It’s mostly fast two track that alternates from flowy dirt with whoops and bowls to bank off of, and faint tracks through the short grass. Some sections seriously feel like you’re ripping straight across a golf course. The dirt tracks are generally smoothed from the rain and when they get too bumpy or rough from a truck getting stuck in the mud, someone makes a new track. Lots of the time, you don’t really need a track at all. The only place where you can normally ride cross-country like this at a good clip is in the desert. Here, you get that same riding freedom, but don’t have to deal with extreme heat or lack of water. Even loaded and two-up, it was some of the most fun off-road riding I’ve ever done.

For the first time in months we weren’t cooking in the desert or freezing in the mountains, the storm front had moved on ahead of us and we had nothing but clear blue skies. We were riding about a hundred miles a day and good camping spots were always easy to find. We could see a spot way up a hill or across a valley from a track we were riding and just blast cross-country towards it. It was so cool. Mongolia feels like a motorcycle play land.

At camps far away from gers or animals, we were surrounded by the stillness of the steppe. A falcon flew overhead and I could hear every beat of its wings clear as a bell. I even managed a bath in a stream.

The Mongolian people are usually friendly and curious about us, but generally more reserved than those we met in the Stans. In Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, the kids would hear us coming down the road and there would be a stampede of them out to the road waiting at the ready to slap us a high five. I never got tired of that. But here we were generally left on our own unless we happened to camp right where a herder was grazing his animals.

Mongolia is a hard place to live. The whole country is situated on a plateau with an average elevation of about 5250 feet (1600 m) resulting in very harsh winters where the temperature drops below 40 C and a blanket of snow covers the grassland. The climate doesn’t allow the Mongolians to grow much in the way of grains or vegetables and there isn’t much food available other than meat. Most people out in the countryside depend wholly on their animals for survival. They eat their meat, wear and make shelters from their hides and fur, and drink their milk. We encountered animals we hadn’t seen before: yaks (which look kind of like gigantic dogs), and two humped camels, better suited for the cold weather than the single humped variety we’d bern chasing all over the road in Africa.

|

26 Aug 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2010

Location: Santa Cruz, California

Posts: 316

|

|

|

Making Tracks across Mongolia II

After days of riding the tracks with no sign of any other riders, let alone our Swiss riding companion, we were stoked to find two other riders, Anthony and Jenny from Israel, both riding Honda CRF 250’s that they’d been riding all the way from Europe for the past five months.

As we rode east, trees appeared on the hills and the four of us found some fuel for fires at night while we talked story of bikes and adventure.

We turned north to find one of the few Buddhist monasteries that survived the Soviet purge of the 1930’s. The track followed a valley and was rougher than what we’d been riding out on the open steppe. The final obstacle was a wide creek. We couldn’t judge its depth the whole way across until a truck came by to show us the path along the shallow gravel bar.

We found a campsite in the saddle of a ridge high above the monastery and bedded down for the night with our usual cadre of four legged neighbors whinnying and neighing into the night. We packed up the next morning and bounced down the hill to check out the monastery as the Tibetan Buddhist monks-in-training went about their morning chants wrapped in robes burgundy and gold.

Approaching Ulaanbaatar, the tarmac returned along with the towns and cars and it was as if waking from a week-long dream in the grassland. The air became was tinged with diesel, a car horn honked, a mini-market appeared, and the spell of the steppe was broken. Given half an excuse I would turn around a ride the same route right back the other direction.

When we arrived at the default overlander flop house in Ulaanbataar, we finally found Jonathan again. A week prior, when we’d last seen him, he’d ridden way up a track that just went to someone’s ger. We’d taken somewhat different routes to Ulaanbataar, but arrived within hours of one another! His front tire was wearing through to the steel belting a week ago, so he sawed off some of the rear tire knobs and super glued them to the worst spots on the front. The prosthetic knobs stayed put during the whole journey. How’s that for a backcountry bodge!

Before arriving in Mongolia, we’d grown a bit road weary and thinking of home, but the time out on the steppe has re-forged the will to wander. I can’t wait to find the next spot to pitch our tent.

|

28 Aug 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Sep 2007

Location: Lutterworth,Midlands, UK

Posts: 573

|

|

That steppe! of the way looks amazing, breathtaking scenery and so unspoilt  ride on

|

13 Sep 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2010

Location: Santa Cruz, California

Posts: 316

|

|

|

Siberia, Interrupted

Siberia is big, and we had a whole lot of its bigness to get across. A carpet of forest stretches to the horizon rolling up and down over the hills. The uniformity of green was rarely broken, other than by the railway and the highway on which we rode. To us, the road was civilization. It was solid. There were other people on it. When we rode just half a mile off the highway and down a muddy track, the forest swallowed us up, as though the trees closed in behind us. It was always something of a relief to return to that tenuous tarmac interruption of the forest.

We’d left Ulaanbaatar with 2400 miles (4000 km) to ride to reach the other side of Russia. We enjoyed a final night of camping out on the open Mongolian steppe before crossing the border where the grasslands slowly graded into pine forests.

We only ride about 200-300 miles a day, so it would take us more than a week to get across Far Eastern Russia. We started off slowly with a stop-off at Lake Baikal. By volume, it’s the largest freshwater lake in world. Which is precisely why we went there, and no other reason at all. We’d heard it was a beautiful place, but we found it unremarkable in every way and basically indistinguishable from any other massive lake that you might run into. We stood and looked at it for a while, felt the water, then got back on the bike and rode away. The beautiful places must have been on the other side. Did I mention that we visited the biggest lake in the world? Yep. Totally touched it. Forgot to take a photo though.

When we finally did get into the forest, it was difficult to find campsites because the trees and undergrowth were so thick. It was the first time since West Africa that I truly wished for a machete strapped to the saddle bag. Our favorite sites ended up being clearings made for rock quarries.

The birch forests usually had more closely spaced trees and thicker undergrowth than the pine forests and we would thread the bike through the trees looking for clear, flat spot to camp.

We usually had plenty of food, but good veggies were hard to find and we had to resist the urge to forage in the woods.

We did our best to find nice picnic spots, but they were as few and far between as nice camp spots. We were quickly missing the outdoor playland of the Mongolian steppe. Here in Siberia, nature was a little more intrusive to our comfort.

The road itself is truly a marvel. To keep the forest at bay and avoid the sucking mud that comes with melting permafrost, there are literally thousands of miles of road tiered up well above the forest floor with tons and tons of gravel. Sometimes we found ourselves riding amongst the treetops, 5-10 meters above the forest floor. The amount of rock that had to be quarried to do this for so many thousand of miles is just astounding.

We met friendly Russians the whole way along who always asked where we were from and where we were going, sometimes wanted to take photos with us, and usually invited us to drink some vodka. One nice guy working at a gas station called us over to his little maintenance shed so that we could do an oil change. He offered us tea and from the shed produced tools and an oil pan for me to use.

Our constant companion was the Trans-Siberian Railway steaming along beside us. At one stage we found a town 10 miles down a dirt track off of the highway. There were markets and banks, offices and apartment buildings; all in what seemed to us to be the middle nowhere. It felt surreal, like an episode of the Twilight Zone. It just seemed mad for all of this to exist down a long dirt track surrounded by forest so far from the highway. But this town was built in the age of the railway, not the highway. The whole town was virtually built around the rail station. We couldn’t help but think how the construction of the rail line must have changed life out here, where the ground is covered in snow for half the year and a muddy bog for the other half. Before the rail line, it would have been incredibly difficult for anything or anyone to get in or out of here.

Eventually it seemed that everywhere that wasn’t the road was a swamp. We had to check carefully what the surface was like before we rode down off the highway to be sure that the undergrowth wasn’t hiding a bog that would have us hopelessly mired.

With the water came the mosquitoes and they came in droves. Our last camp was so bad that Jamie kept her helmet on until we finally dove into the sanctuary of the tent. Anytime I uncovered the cook pot for even a second, hundreds of them would kamikaze to their deaths into the food. The whole thing must have been a comedic site, both of us bundled like ninjas, Jamie running around in her fogged up helmet, screaming ‘breach’ every once in awhile when a mosquito found its way inside, and me trying to stir a pot with the lid still on and regularly smacking myself in the face. As the sun got lower they got worse. I’ve been in places with bad mosquitoes before, but this was another level. It was difficult to breath without inhaling a cloud of the little suckers.

We rode more than 400 miles the next day to reach Vladivostok rather than camp in another mosquito cloud. The last time I touched the Pacific Ocean was in California and now I got to dip my toes in on the other side of it. I’d been hopeful to find a surf shop and some waves to ride near Vladivostok. The hope of it had spurred me forward on plenty of days. We found some great cobble reef/point setups where I’d seen photos of pretty good waves on the Internet. However, it seems that you’d have to be pretty lucky to get a big enough swell here in September and we only saw the most micro of waves peeling along the raised bars of cobbles.

The last couple of days on the road, Dyna Rae had been trying to bog at about ¼ throttle. I assumed that it was some gunk clogging a jet in the carburetor. On the night that we rode into Vladivostok it had gotten bad enough that she was pretty difficult to ride in city traffic. I was happy to make it to a guesthouse and collapse for the night. When we packed up to move to a cheaper place the next morning, she died under any throttle. Fortunately it wasn’t far to the other guesthouse and the first half was downhill. Unfortunately the second half was uphill, and so there Jamie and I were, grunting and heaving the fully loaded bike against gravity inch by inch, towards a massive soviet-era submarine.

I took the carburetor apart and cleaned it up shiny but was dismayed when my efforts had no effect whatsoever. I puzzled over it for a day or so before I resolved that something mechanical must be going wrong with the fuel delivery. I had a close look at the needle that I’d replaced in Romania and found it and the spacer very worn. When I compared the needle to the old one I’d replaced, I noticed that its taper was slightly thicker at the end, allowing less fuel into the chamber. It seemed that as the spacer wore down, the unexplainably thicker needle eventually stopped letting enough fuel in to keep her running. I put the old thoroughly worn needle back in, the bog disappeared and she roared back to life. It’s amazing that this didn’t happen in the middle of the Siberian forest mosquito hell. She was tired and coughing, but somehow just didn’t quit until we made it all the way to the finish line at Vladivostok. Thank you Dyna Rae.

We’d run out of east to ride so it was time to turn south to head for China. As nicely as we asked, the Chinese simply would not let us go riding our bike around willy-nilly across their country. We’d need to have a full time guide, a Chinese driver's license, and a bunch of other stuff that made the whole escapade far too structured and costly for our taste. The smart thing to do arriving in Vladivostok with a clapped out bike and nowhere to ride would be to sell it, not to haul it back across an ocean, but I just couldn’t manage to let her go.

This little machine has been home for two years and carried Jamie and me back and forth across three continents more than 60 thousand miles. Her chain is sagging, sprockets worn down to the nub, rotors scored, bash plate thoroughly dented, front wheel wonky from our crash in Tajikistan, tires nearly bald, carb bodged together, and she’s still carrying a quarter pound of dust from the Sudan Desert. She’s no spring chicken and drinks some oil as the parts in her worn cylinder head begin to show their age, but just keeps thumping along. I know every nuance of every sound she makes and how it changes when the temperature or the altitude rises, her valves get loose, or her air filter is clogged. I can feel the difference in how her gears mesh together when the oil gets dirty. I’ve put every scratch on her and twisted every bolt myself. I love her flaws and quirks as much as her attributes, because they all add up to my bike.

I cleaned her up and arranged to get her in a container headed for Vancouver at a cost that makes no sense given the state of the bike. Now we’re on the bus. No dust in our face or mosquitoes in our dinner. No sore behinds. We climbed a mountain and my face didn’t get cold and when a rain shower passed we didn’t get wet. I didn’t smell the trees when they changed or feel the bumps in the road. It was comfortable. How lame.

|

29 Sep 2015

|

|

Registered Users

HUBB regular

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2013

Location: Key West, Florida

Posts: 26

|

|

|

I am very glad you didn't sell the bike. No explanation needed. It's absurd that a motorcycle can become your home, but it really can.

Happily the story isn't yet finished.

|

1 Oct 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2010

Location: Santa Cruz, California

Posts: 316

|

|

|

but it does feel more like a comedy now :-)

|

1 Oct 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2010

Location: Santa Cruz, California

Posts: 316

|

|

|

The Slow Road through China

China wins no points in the moto-fun department, refusing to let us enter with our beloved motorbike  , forcing us to endure the four-hour bus ride from Vladivostok, Russia to Hunchun, China. We drove over the landscape in a sealed container barely awake, rather than riding through it with our senses alight. We needed to fix this situation, whether China was onboard with the moto-hobo lifestyle or not.

The cheapest thing that we could find was a little moped looking thing. She’s 48cc’s of fire breathing Chinese muscle. Two of those ought to do for us, but the shop only had one. Two-up on a 48cc across China – was this even possible? We were determined to find out.

Buying stuff in China is pretty cheap. They invented stuff-making here. We got the bike, along with a shiny top box, two helmets, and a lock chucked in, all for a song of a deal. I still don’t even know the make of the bike. We grabbed a couple backpacks to stuff our stuff, I assembled a comprehensive tool kit (mostly zip ties and duct tape), and that was it, ready ride across China.

On our diminutive machine, wearing our Chinese helmets with sunglasses on, we’re virtually undetectable as foreigners, so we fly under the radar at any police checkpoint. They don’t even look twice at us as we ride right by. Before we arrived I’d read on a website written by an American expat in China that you don’t need a Chinese license or a plate for a bike under 50cc’s. I don’t really know if that’s true or not, but so far everyone just ignores us.

You might think we’re being a bit cavalier about all this and you’d be correct. Even after all we’d gone through on this trip up to now, wobbling off on the little bike felt half insane. I didn’t even know if we could make it up a hill with the both of us until we got to the first one 30 km away from the town. She’ll get to the top of a mild grade but she’s none too happy about the climb. We’re basically about half a rung above a bicycle on the vehicle hierarchy.

For the first three days riding, something broke every day. We just hopped from one little shop to another. Little bike shops are absolutely everywhere and there is always someone to help out. Within the first 200 km the rear tire delaminated. We retreated to a shop to get a new one that is surely better quality, but it was bigger and rubbed the fender every bump we hit. We absolutely mangled the fender to provide some more clearance and iteratively stopped at one shop after another borrowing tools to mangle it even more. Finally, with the pre-load on the springs cranked all the way up, an over-sized knobby tire, and a rear fender that looked like a piece of modern art, we had a fully off-road capable machine. Mostly because I can just lift it up to carry it over any really big bumps.

The first few days of riding we spent most of the time winding through lovely, mountain roads with very little traffic, flanked by trees ablaze with the colors of fall. I was in a state of disbelief that this was actually working; that we were really going to ride this thing, carrying everything we needed, 3 thousand miles across China. When a storm came through we found our first hard day of riding ducking under bridges as the showers came and went during the day. We donned the rain gear that we bought in Hunchun for $3 dollars each. I looked like I was wearing a set of hefty bags and Jamie looked like she was about to be sent off to the school bus carrying a Hello Kitty lunch box.

As this trip has progressed, I’ve become increasingly more useless to get where we’re going and Jamie has become ever more essential. In Russia, Jamie learned the Cyrillic alphabet so that we could read signs and she even made a fair stab at learning Russian. The first time we got into an elevator in China, Jamie started speaking Mandarin to the lady next to us. My girlfriend speaks Chinese!? Jamie had lived in Taiwan for two years, so I figured she’d picked some up, but I still couldn’t help being amazing standing there listening to her. I can say hello. That’s it.

Additionally, Jamie is now the route planner and navigator, since I no longer have the phone mounted up on the front of the bike. So pretty much all I do now is drive the bike and say hello a lot. Ni Hao.

Planning routes in a huge country on a slow bike is a lot more complex than a big bike, since we have to take care to avoid the major roads where we’d quickly be mowed down by trucks. We pretty much have to plan as though we were on bicycles, following the smaller provincial roads through the countryside and trying the skirt as many of the big cities as possible. Riding all day long we can only manage about 200 km a day. We make about 40 km per liter of fuel (100 mpg), but the tank only holds 3 liters. At the first gas station, we found a 4-liter plastic container, which has been our auxiliary tank ever since, giving us a range of nearly of about 280 km.

People in China generally drive like idiots; going the wrong way on the shoulder, launching up onto the road without even slowing down at the intersection, weaving all over the lane in a three wheel cart while talking on a phone, performing a left turn by slowly mowing through oncoming traffic. In some ways the demeanor on the road has a distinctly African feel. All of this said, there is rarely any mal intent or aggression behind any of it. People are used to lots of motorbikes everywhere and are genuinely mindful of us on the road. Unless they need to turn left and you happen to be coming from the other direction – in that case, avoiding them is your problem. It’s taken me about a week to get into the swing of things and to stop being the angriest white man in China.

I wanted to come to China because I thought it would be strange and so far I’ve not been disappointed. One night we set out in a town looking for food and found a lady frying up tofu in a street cart. Awesome! Except when it was ready, she slathered it in some gray brown sauce that seriously smelled like it had come from a break in the sewer line. This was my introduction to a Chinese classic, called ‘Stinky Tofu’. The stink has nothing redeemable about it like stinky French cheese for instance. It seriously smells like an outhouse. It’s radical. I can’t believe people eat it. Another night, we checked into a hotel and quickly noticed that it was cooking hot everywhere in the building even though it was cold outside. It seemed that we’d inadvertently checked into some spa-hotel place with the idea to cook the ailments out of their guests. Every time we left the lobby, we had to check our shoes in and head upstairs in funny little slippers. I wasn’t into it.

The reason we ended up at Hotel Hotness was that we’d been told that only certain hotels are licensed to serve foreigners. When we’d tried to check into a simple guesthouse in a small town, the police quickly arrived to tell us that we had to leave the town. The place they wanted us to go was 80 km away and it had just started getting dark. We flat out refused to go on the grounds that it was too dangerous to ride off now. They said that we were in a disputed autonomous region called Liao Ning Province and it was for our own safety that we should leave. So, leave, and go hurtling through the darkness on the highway on our tiny little bike. Safely. That made perfect sense.

We went back and forth a few times until the police finally agreed that they would call a truck to drive us out of town with the bike. A free ride - stoked! These guys really did want us out of town! During the time we were waiting for the truck, half the town had turned up to the hotel to meet the crazy foreigners riding the silly little bike. No one seemed the least bit threatening to our safety other than a guy who tried to make us eat some chicken feet. Those looked pretty dangerous. We’ve since learned that such a license to serve foreigners used to be needed, but no longer - the requirement was revoked in 2003. However, some local police still tell guesthouses that they need this license, which doesn’t exist. It’s all down to the whim of the local police and we’ve also learned some local jurisdictions have outlawed foreigners from being in their cities altogether.

With a population more than 2 billion strong, China is utterly filled to the brim with people. We run into big towns and full-on cities constantly. For us, it’s been a dramatic change from the sparsely populated regions in Mongolia and Siberia. Signs of the fastest growing economy in the world are everywhere from massive infrastructure projects to huge housing developments. Explosions of fireworks regularly punctuate the afternoon as fireworks heralding the completion of a new building. The first time it happened nearby I nearly ran for cover. We rode beneath expressways tiered up with more pillars that we could count spanning massive wide valleys and saw the skylines of town after town edged with scores of brand new skyscrapers and more on the way up. All of this growth requires plenty of energy, but they do seem to keep their nuclear power a bit close for comfort.

Sites that preserve China’s heritage persist right alongside the boomtowns. Riding towards Beijing, we couldn’t pass up the opportunity to go for a hike along the Great Wall. It had taken us more than a week to reach Beijing riding from the Russian border and we were more than happy to spend some time moving on our feet rather than on our butts.

We set out up onto the wall from the village of Gubeikou, where the wall is in a pretty ruinous state, but there are no tourist crowds like there are at some of the restored sections of the wall. It was a harder hike than we’d guessed climbing and dropping along ridgelines on an uneven surface of cracked and dislodged stones that formed this wild section of the wall.

Along the way, we met an Australian couple Dan and Nadine, also hiking the same section of The Wall, on a trip out from their home in Kuala Lumpur. They were the first foreigners we’d seen the entire time in China.

We hiked towards a restored section at a place called Jinshanling, before retreating the same direction that we’d come just before dusk. On the way out, we’d scoped out a good guard tower that we’d commandeer for the night.

We’d sent our warmest sleeping bag back to California with the bike, and the temperature dropped low enough that we spent a cold, angry night trying to find some warmth at bottom of our sleeping bags. I had both of our raincoats over top of my sleeping bag in an effort to retain some heat. From 2 AM onwards, Jamie and I were both barely in and out of consciousness and just waiting for sun to rise. Finally the stars began to fade as the sun rose behind the hills. As tough a night as it was, it still felt worthwhile when we caught the morning view of the wall in the golden glow of sunrise.

We’d ridden more than a 1200 miles to reach Beijing and still have double that distance to go to reach the other side of China. Jamie is practicing her Chinese and I’m trying to learn to navigate our minuscule moto through the city chaos like a Zen Master rather than a confused tourist. The journey has slowed to a snail’s pace, but at least we’re back on two wheels with the wind in our face. It still seems like a long way before I’ll get some bugs on my board again.

|

2 Oct 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Aug 2013

Location: Sunderland

Posts: 242

|

|

|

Really enjoyed reading your posts on your a endure shame

|

2 Oct 2015

|

|

Registered Users

HUBB regular

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2013

Location: Key West, Florida

Posts: 26

|

|

|

This is really becoming surreal. I thought you were following the bike and now you are riding a gruesome moped across China? You spent the night on the Great Wall? My head is spinning. Nothing is impossible. I feel fairly certain you will soon cross paths with Salvador Dali who isn't actually dead but tonking around a village in China, unbeknown to us all. Please keep taking pictures or nothing will be believed.

|

8 Oct 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2010

Location: Santa Cruz, California

Posts: 316

|

|

|

I thought it was strange to find a dude with a pointy 'stache speaking Spanish in the middle of China!

|

8 Oct 2015

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2010

Location: Santa Cruz, California

Posts: 316

|

|

|

Edges of Africa - Part II

Hey guys - forgot to post up the latest video installment of the Africa journey - please enjoy..

|

|

Currently Active Users Viewing This Thread: 1 (0 Registered Users and/or Members and 1 guests)

|

|

|

Posting Rules

Posting Rules

|

You may not post new threads

You may not post replies

You may not post attachments

You may not edit your posts

HTML code is Off

|

|

|

|

Check the RAW segments; Grant, your HU host is on every month!

Episodes below to listen to while you, err, pretend to do something or other...

2020 Edition of Chris Scott's Adventure Motorcycling Handbook.

"Ultimate global guide for red-blooded bikers planning overseas exploration. Covers choice & preparation of best bike, shipping overseas, baggage design, riding techniques, travel health, visas, documentation, safety and useful addresses." Recommended. (Grant)

Led by special operations veterans, Stanford Medicine affiliated physicians, paramedics and other travel experts, Ripcord is perfect for adventure seekers, climbers, skiers, sports enthusiasts, hunters, international travelers, humanitarian efforts, expeditions and more.

Ripcord Rescue Travel Insurance™ combines into a single integrated program the best evacuation and rescue with the premier travel insurance coverages designed for adventurers and travel is covered on motorcycles of all sizes.

(ONLY US RESIDENTS and currently has a limit of 60 days.)

Ripcord Evacuation Insurance is available for ALL nationalities.

What others say about HU...

"This site is the BIBLE for international bike travelers." Greg, Australia

"Thank you! The web site, The travels, The insight, The inspiration, Everything, just thanks." Colin, UK

"My friend and I are planning a trip from Singapore to England... We found (the HU) site invaluable as an aid to planning and have based a lot of our purchases (bikes, riding gear, etc.) on what we have learned from this site." Phil, Australia

"I for one always had an adventurous spirit, but you and Susan lit the fire for my trip and I'll be forever grateful for what you two do to inspire others to just do it." Brent, USA

"Your website is a mecca of valuable information and the (video) series is informative, entertaining, and inspiring!" Jennifer, Canada

"Your worldwide organisation and events are the Go To places to for all serious touring and aspiring touring bikers." Trevor, South Africa

"This is the answer to all my questions." Haydn, Australia

"Keep going the excellent work you are doing for Horizons Unlimited - I love it!" Thomas, Germany

Lots more comments here!

Every book a diary

Every chapter a day

Every day a journey

Refreshingly honest and compelling tales: the hights and lows of a life on the road. Solo, unsupported, budget journeys of discovery.

Authentic, engaging and evocative travel memoirs, overland, around the world and through life.

All 8 books available from the author or as eBooks and audio books

Back Road Map Books and Backroad GPS Maps for all of Canada - a must have!

New to Horizons Unlimited?

New to motorcycle travelling? New to the HU site? Confused? Too many options? It's really very simple - just 4 easy steps!

Horizons Unlimited was founded in 1997 by Grant and Susan Johnson following their journey around the world on a BMW R80G/S.

Read more about Grant & Susan's story

Read more about Grant & Susan's story

Membership - help keep us going!

Horizons Unlimited is not a big multi-national company, just two people who love motorcycle travel and have grown what started as a hobby in 1997 into a full time job (usually 8-10 hours per day and 7 days a week) and a labour of love. To keep it going and a roof over our heads, we run events all over the world with the help of volunteers; we sell inspirational and informative DVDs; we have a few selected advertisers; and we make a small amount from memberships.

You don't have to be a Member to come to an HU meeting, access the website, or ask questions on the HUBB. What you get for your membership contribution is our sincere gratitude, good karma and knowing that you're helping to keep the motorcycle travel dream alive. Contributing Members and Gold Members do get additional features on the HUBB. Here's a list of all the Member benefits on the HUBB.

|

|

|

42Likes

42Likes

The road eventually turned into a smooth two track that we could just flow along in second gear, crisscrossing the turquoise stream periodically and railing through a turn here and there. There was no other traffic at all other than two cyclists that we saw going the other direction. Even with our broken spring, it was a super fun road to ride – pretty much the perfect sort of terrain for a dual-sport bike. We found an epic camp spot for the night in a patch of lush grass right beside a crystal clear stream. By the time we’d made camp, a light rain had started, but Mike and I stood outside anyway, cooking dinner and drinking whiskey. This was what we'd come for.

The road eventually turned into a smooth two track that we could just flow along in second gear, crisscrossing the turquoise stream periodically and railing through a turn here and there. There was no other traffic at all other than two cyclists that we saw going the other direction. Even with our broken spring, it was a super fun road to ride – pretty much the perfect sort of terrain for a dual-sport bike. We found an epic camp spot for the night in a patch of lush grass right beside a crystal clear stream. By the time we’d made camp, a light rain had started, but Mike and I stood outside anyway, cooking dinner and drinking whiskey. This was what we'd come for.

ride on

ride on

Linear Mode

Linear Mode