|

|

Entering Russia from Latvia was a minor exercise at the border. The visa was stamped as well as my passport, giving me license to ride my motorcycle nearly anywhere in Russia for the next 30 days. I had to fill out a Customs Form, declaring things like my cameras and motorcycle, estimating their value. There was some standing around while Border Ivan came back from lunch or a power meeting, but eventually a computer spit out the needed document allowing entry of my vehicle, a Kawasaki 650 KLR. One wrinkle that would present a minor problem exiting 30 days later was the different engine number and VIN for the motorcycle, Border Ivan entering the same VIN on both lines of the form instead of writing the different number. The entry process took just over an hour and one-half, which was less than trying to get into places like Egypt or India. I entered Russia without a Carnet de Passage, and insurance was not required.

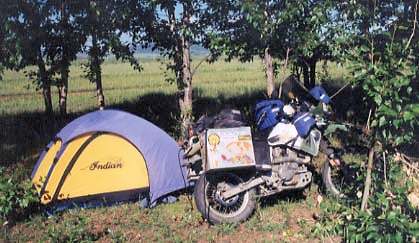

While it is possible to stay in a hotel every night while crossing Russia, I carried my tent and sleeping bag. Hotels were often expensive, especially in the large cities. The tourist infrastructure is slowly developing in Russia, but is nowhere on par with Europe. Sometimes I was able to find a roadside sleeping room for as little as $2.00 US, or a better "motel" for $10.00 - $12.00. The quality ranged from a sagging single bed made from plywood in a shared room to a double bed with fresh sheets in an upscale room with television and private bath for $20.00. I tried to stay out of the big cities where rooms were readily available for $50.00 to $150.00, and I lost time trying to find them, often overpriced for their value. If I got too far into the day and could not locate a cheap sleep for the night, I would head for the woods and pitch the tent. The price was always right (free) and I never had to listen to the nocturnal sounds in the next room through thin walls or the clanking of the water pipes. One morning in the woods I woke to the sound of a cuckoo bird, or something very similar. |

|

| Moscow was expensive, and huge. Moscow bike friend Vladimir Zyablov (www.shop.moto.ru) interviewed me for a Russian motorcycle magazine (MOTO), then introduced me to "BIKE CENTER," owned and operated by Russia’s oldest motorcycle club, The Night Wolves. Their Harley-Davidson shop, restaurant, disco, theatre, and bar were a huge complex modeled in Mad Max deco. It was the most impressive biker display I have seen anywhere in the world, and a credit to the Night Wolves that they could "out-do" other biker groups and yuppie restaurateurs around the world.

Russian people were far friendlier than I expected. Having lived through the Cold War and various media campaigns in the USA press, I did not expect them to be so friendly. People were always surprised to discover I was an American, traveling solo by motorcycle around the world. Most of the motorcycle travelers they meet are from Europe, generally German or Swiss. The Russian people frequently asked to have their picture taken with me. An even bigger surprise for me was how often they were able to identify me as an American Indian. They would ask shyly if I was, and when I said, "Yes," their reaction was occasionally overwhelming. I was more warmly welcomed by Russian people, as an American Indian, than I have been in America. It was really quite surprising. The lady in the picture above insisted her husband take this picture of us together. She wanted me to mail her a copy when I got home, which I will, but I thought it would be quicker to post it here on my website. The road police were very active throughout Russia. Several times I saw hand held radar guns being used. Usually on the road into and out of larger towns there were police checkpoints. I was asked to stop at several of these checkpoints where I had to show my passport, International Driving Permit, or visa. Once the officers required me to come into their blockhouse where they wrote down by hand the numbers off my visa into a well used notebook, borrowing my pen because they did not have one. Most often the police were just bored and wanted to look at my motorcycle when they flagged my down. I never felt easy at these roadside stops, as there was always a second officer with his hand on a gun, watching the first officer check my papers. While I was able to get them to smile and laugh, I had the feeling it would not take much to get them to point their gun at me and pull the trigger, especially the ones with bloodshot eyes and cuts on their faces from the previous night’s fistfight and vodka consumption. The Road Police Ivan's looked a lot like Military Ivan's from not long ago. |

|

This map shows the world, with the "red" being Russia. It was a surprise to ride every day for a week, and discover I had only gotten about one-third of the way across the country. There was a section of nearly 1,000 miles where the road did not exist. In this area there is a swamp. Trains cross it, and there are some service roads, but most cars, trucks and motorcycles take advantage of the train by being loaded onto platform cars and making the trip in two nights and three days. I "tested" my Kawasaki in some of the swamp, and immediately determined it was far to heavy for the mud, water and slop. For me to ride through this section would have required that I send all of my luggage, unaccompanied, by train to the end of the line, while I spent the next two weeks flogging the motorcycle through the Siberian swamp. In my short life I have seen enough mud, water and slop to fill the rest of what is ahead of me, so I opted to put the motorcycle and myself on the train. That was an adventure in itself, as I had to ride illegally to accompany the bike, maybe best described in a future short story. The train ride included elements such as the police, prostitutes, bad food, toilets that were clogged, beer/vodka, guns, gambling, oven-like temperatures and a wreck. One motorcycle friend said that for her the ride on the train was the biggest adventure of her entire ride across Russia. For me it constituted a major challenge in for my patience. I had come to Russia to ride roads, not rails. As I saw mile after mile of the land pass by from the open door of the luggage car, where I passed my days and nights, I felt the loss of missing a great section of this huge land. Several years ago I had read a book about some bicyclists who had made the journey across the swamp. Their story was one of misery of having to find food, slapping bugs, and carrying their bicycles much of the way because of the impossibility of pedaling through the muck. To do the same on the motorcycle, given the time I had, would have been impossible. I saw sections of gravel road along the way that would have been easily ridden over, but then I would see other sections of water covering the road, often 3-6 feet deep, because the month of June and July had been especially wet (a lot of rain), so knew those sections would be impassable until I could flag down a truck or build some kind of raft. As I looked at those sections, knowing them to have more mosquitoes per square inch than India has people in their entire country, I would smile to myself, sip my beer and wonder why anyone, including myself, would even contemplate such a land crossing.

David McSkimming, pictured above, was from Australia, where they do not have many "swamps," so he did not have a clear picture of what lay ahead of him. He was going to try to cross the swamp by riding his motorcycle. He had met an English rider who claimed to have ridden across, so figured he could also make the ride. A friend of mine, Dave Barr, rode his Harley-Davidson across, but Dave is an exceptional adventurer. He did it in the winter, when the swamp was frozen. I still wonder if McSkimming made the complete ride, or, like me, bagged it after the first 100 meters of muck and pitched his Honda onto the train. Once I arrived in Vladivostok, I was faced with the problem of getting the motorcycle crated, then onto an air cargo flight to Los Angeles, where I would collect it and complete my fourth ride around the world. I used a company (Links, Ltd) in Vladivostok to crate the bike. Their General Manager spoke English, and the company had previously crated other motorcycles for air cargo. Their email address, and telephone, 4232 220 887, in Vladivostok. They were very efficient, made the crate to specifications given by the air cargo shipper, and delivered the box, unassembled, to the airport. The price was $160.00 for the box and $70.00 for the delivery. At the airport, I placed the motorcycle on the base of the box, and took it apart, removing wheels, front fender, compressing the forks, and disconnecting the headlight/speedometer pod, to get it to fit inside the much smaller box. Once that was done, the Links workers nailed the box together. A forklift moved the box to a scale where it was weighed and I was billed $1,253.00 US, plus some odd change (which I paid), to get it shipped. There were several documents that needed to be filled out, and a payment to be made ($3.00) several miles away to secure a stamp on an export form. The whole process took about 8 hours, and I could not have done the paperwork part without the help of one of the Links workers who knew where to collect and drop off the forms. The Customs Office required the crated motorcycle to spend 24 hours sitting in a warehouse before it could be shipped out. |

|

|

|||

|

| ||

|

Copyright © Dr. Gregory W. Frazier 1999- All Rights Reserved.

Thoughts and opinions expressed here are those of the author, and not necessarily Horizons Unlimited

|