45Likes 45Likes

|

|

8 Oct 2011

|

|

HU Founder

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Dec 1997

Location: BC Canada

Posts: 7,364

|

|

The Clancy Centenary Ride 2012-2013

The Clancy Centenary Ride 2012-2013

The Clancy Centenary Ride 2012-2013

Celebrating 100 Years Of Circling The World By Motorcycle

In 1912 Carl Stearns Clancy and his riding partner Walter Storey set out to become the first motorcyclists to “girdle the globe.” Using two of only five Henderson motorcycles produced by the famed Henderson Motorcycle Company in 1912, the duo left Philadelphia and started their land trip from Dublin, Ireland.

After a frightful crash on Day 1 and miserable weather in October and November, Storey left the 21 year-old Clancy in Paris, and Clancy soldiered on alone.

Clancy spent the next months riding south to Spain, and then across north Africa, only to be halted before attempting to cross India. Undeterred he shipped his motorcycle to Ceylon where he toured from some days, and then shipped again to Penang. Once there he discovered there was no road to Singapore, so it was back on to a boat for Hong Kong, Shanghai and Japan.

Landing in San Francisco, Clancy began what he called the most difficult part of his ‘round the world ride: San Francisco, California to Portland, Oregon, and then across the northern part of the United States to return to New York. His journey lasted 10 months and he had ridden over 18,000 miles.

Two serious Irish adventurers have decided to organize a global re-enactment of the Clancy record setting ride around the world. Feargal O’Neill and his colleague Joe Walsh, in conjunction with the motorcycle traveller’s website Horizons Unlimited, have announced the Clancy Centenary Ride for 2012-2013. According to O’Neill, “I feel that there is a duty on us modern-day motorcyclists to do our bit to honour the memory of this great pioneer of our sport.

The recent release of the book MOTORCYCLE ADVENTURER, a 16 year research project by global road rider (five times around the world) Dr. Gregory W. Frazier, has brought light to the incredible journey made by Clancy. ‘round the world riders can now follow the original route and incredible ordeal made by one of the first real motorcycle adventure riders.

The plan, as explained by O’Neill, is for Horizons Unlimited travellers to retrace the route Clancy made in 1912-1913 on any make and model motorcycle. The riders can follow Clancy’s route for one mile or 1,000’s, depending on their time and commitment. There will be no entry fee and each entrant can join with a group or go solo over what can be traversed of the original route.

Dr. Frazier has agreed to organize and join in the American leg, from San Francisco to New York. Frazier has already researched much of the original route and even suggested a 1912 Henderson may join the much publicized event.

Carl Stearns Clancy had the motorcycle ride of a lifetime, one which modern day riders can only dream about. The next thing closest is to join with other ‘round the world aficionados and Horizons Unlimited to celebrate 100 years of circling the globe.

Bookmark the Clancy Centenary Ride and join or follow one of the world’s greatest motorcycles adventures whether through cyberspace or on the ground in the ride around the world.

More in the Motorcycle USA Article by Greg Frazier

The book is available on Amazon!

More information to come.

What about you? Interested in joining in?

__________________

Grant Johnson

Seek, and ye shall find.

------------------------

Inspiring, Informing and Connecting travellers since 1997!

www.HorizonsUnlimited.com

|

8 Oct 2011

|

|

Contributing Member

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Nov 2003

Location: Netherlands

Posts: 639

|

|

|

I found Clancy and Storey had a sea-crossing from England to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Where can I get the route they travelled in the Netherlands and the countries next to it ?

I would be interested to ride part of their route in this part of Europe.

__________________

Jan Krijtenburg

My bikes are a Honda GoldWing GL1200 and a Harley-Davidson FXD Dyna Super Glide

My personal homepage with trip reports: https://www.krijtenburg.nl/

YouTube channel (that I do together with one of my sons): motormobilist.nl

Last edited by jkrijt; 22 Oct 2011 at 08:56.

|

9 Oct 2011

|

|

HU Sponsor

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Sep 1999

Location: Yellowtail, Montana USA

Posts: 297

|

|

|

On the Clancy Trail now

I followed the Clancy Trail backwards from Billings, Montana to Livingston, Montana this week, and then the side trip up to Gardiner at the entrance to yellowstone. Now picking up another section from Portland, Oregon to San Francisco. He had a tough ride over these sections that are now paved. As I rode to Portland I was reminded of how he wrote one day he fell/crashed 17 times!

I'll be doing a Clancy presentation October 14 and 15 at the California HU Meeting, sharing some of the "secrets" of his ride around the world not in the book.

Cheers,

Dr. G, on the Clancy Trail

__________________

Sun Chaser, or 'Dr.G', Professor of Motorcycle Adventure at SOUND RIDER magazine. Professional Motorcycle Adventurer/Indian Motorcycle Racer/journalist/author/global economist/World's # 1 Motorcycle Adventure Sleeper & Wastrel

Soul Sensual Survivor: www.greataroundtheworldmotorcycleadventurerally.co m

|

20 Oct 2011

|

|

Contributing Member

HUBB regular

|

|

Join Date: Jul 2009

Location: Ireland

Posts: 39

|

|

Quote:

Originally Posted by jkrijt

I found Clancy and Storey had a sea-crossing from England to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Where can I get the route they travelled in the Netherlands and the countries next to it ?

I would be interested to ride part of their route in this part of Europe.

|

Hi Jan,

Thanks a million for your interest in this run. This is exactly the kind of response I was hoping would emerge. Our idea is to have a reproduction made of the pennant which was given to the guys in 1912 and which they proudly displayed when posing for photographs at various stages of the trip. This could be passed from person to person signifying the progress of the journey. Where sea-crossings or other obstacles, eg political situations, are in the way the pennant could be sent by post or courier service to a participant in the next area the route passes through.

There are areas/countries where Clancy was unable to travel through in 1912/1913 for one reason or another. My view, and I stress this is just my view, is that if there are people in these places who are willing to traverse areas today that Clancy couldn’t on the original trip, then that’d be great. For instance, I know that there are HU members in countries such as Turkey and India and I imagine that some might like to do for Clancy today what he was unable to do back then. I fully acknowledge that others would hold the view that the 2012/2013 trip should mirror the original one as closely as possible and I will be happy to go with whichever option the majority considers appropriate.

Hopefully as more people come on board over the next year we will gradually join up all the dots.

Feargal O’Neill

|

2 Nov 2011

|

|

HU Sponsor

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Sep 1999

Location: Yellowtail, Montana USA

Posts: 297

|

|

|

USA Start Date Announced: June 2, 2013

June 2, 2013 is the planned Start Date for motorcycle adventurists wishing to join part, or all, of the USA portion of the Clancy Centenary Ride (San Francisco - New York).

While Clancy originally wrote that he departed by ferry boat to Oakland at 5:00 PM, our departure will be in the morning after a media event and photo op.

We will be asking my adventurous colleagues at CITY BIKE ( www.citybike.com) magazine to assist in arranging for a wild send-off from the waterfront.

Dr. Gregory Frazier

Chief, World Adventure Affairs Desk, CITY BIKE magazine

__________________

Sun Chaser, or 'Dr.G', Professor of Motorcycle Adventure at SOUND RIDER magazine. Professional Motorcycle Adventurer/Indian Motorcycle Racer/journalist/author/global economist/World's # 1 Motorcycle Adventure Sleeper & Wastrel

Soul Sensual Survivor: www.greataroundtheworldmotorcycleadventurerally.co m

Last edited by Sun Chaser; 2 Nov 2011 at 04:45.

|

8 Dec 2011

|

|

Registered Users

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Mar 2006

Location: West London

Posts: 920

|

|

I notice from this map,

that the route passes through London. While not strictly authentic to the precise route, can I suggest a stop at the Ace Cafe? In its time it's seen many a motorcycle adventure, be it the Ton-Up Club to a Cat On A Bike. The Ace always has a crowd of bikers and organised meets happen practically every day. Their London to Brighton ride pulls in thousands of bikers from around the world. While Clancy predates the Ace by several decades I can imagine it would be just the place he would have headed for had their histories coincided.

As it's become my local I'm more than happy to speak to them to see what could be organised. I can imagine an amazing convoy from the Ace to Tilbury, which could attract many a biker, especially if it was at the weekend.

__________________

Happiness has 125 cc

|

5 Jan 2012

|

|

Registered Users

New on the HUBB

|

|

Join Date: Jan 2012

Posts: 1

|

|

|

Clancey Henderson Ride

Very interested in taking part in this Historic re-enactment. Naturally, I would ride a Henderson for this event. I just ordered the Clancey book! Let me know how to get involved.

John in USA

|

2 Apr 2012

|

|

Registered Users

New on the HUBB

|

|

Join Date: Apr 2012

Location: British Columbia

Posts: 1

|

|

|

USA route details?

Are there any route details for the USA leg yet? I'd like to find a way to join in for part of the west coast portion on my 1913 Henderson.

Quote:

Originally Posted by Sun Chaser

June 2, 2013 is the planned Start Date for motorcycle adventurists wishing to join part, or all, of the USA portion of the Clancy Centenary Ride (San Francisco - New York).

While Clancy originally wrote that he departed by ferry boat to Oakland at 5:00 PM, our departure will be in the morning after a media event and photo op.

We will be asking my adventurous colleagues at CITY BIKE ( www.citybike.com) magazine to assist in arranging for a wild send-off from the waterfront.

Dr. Gregory Frazier

Chief, World Adventure Affairs Desk, CITY BIKE magazine

|

|

3 Apr 2012

|

|

HU Founder

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Dec 1997

Location: BC Canada

Posts: 7,364

|

|

Welcome to HU Pete!

I'd love to see that Henderson, and you will be VERY welcome on the ride.

Details are a ways off yet, but do make a point to subscribe to this thread - see thread tools above the thread - then it's easy to keep up on what's happening.

I suspect the ride won't be coming this far north (Canada) so assume you'd trailer it down to say SF to start?

__________________

Grant Johnson

Seek, and ye shall find.

------------------------

Inspiring, Informing and Connecting travellers since 1997!

www.HorizonsUnlimited.com

|

4 Oct 2012

|

|

Registered Users

New on the HUBB

|

|

Join Date: Sep 2007

Location: UK

Posts: 6

|

|

|

Clancy Run. Starting date etc.

The UK leg of the run will start at Glasgow on 27th Oct at 9am.

The first day will end at a campsite in North Wales near Chester.

We aim to be at Tilbury docks, London on Sunday evening, 28th Oct.

I will update this site with more information such as the exact start place, towns we will pass through and the campsite location as this information becomes available.

You can do as much or as little of the route as you please.

Buena Ruta and look forward to seeing you!!

|

21 Dec 2012

|

|

Registered Users

New on the HUBB

|

|

Join Date: Dec 2012

Location: northern California

Posts: 9

|

|

|

I'm very interested in riding the SF to NYC leg next year. Is there a specific thread or site for that?? I searched but did not find anything. I live near SF, recently retired, and have a suitable bike so the ride seems ideal. Have done some MC touring and a lot by bicycle, have beed an avid two wheel rider since the '70's....

|

22 Dec 2012

|

|

HU Sponsor

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Sep 1999

Location: Yellowtail, Montana USA

Posts: 297

|

|

|

USA Schedule

June 2, depart SF, arrive in NYC June 21. Details TBA early January. Watch here. We are waiting for some final feedback on "hosts" along the way. CITY BIKE is our "Send-Off" host in SF.

Regards,

Dr. Gregory W. Frazier

Chief, World Adventure Affairs Desk, CITY BIKE Magazine (now on sabbatical)

"FRAZIER PARKED

Dr. Gregory W. Frazier, Chief of the World Adventure Affairs Desk for CITY BIKE, has been granted sabbatical leave from his desk duties. He will be continuing his research on the transcendental relationship between adventure motorcycling, extreme martial arts and the miteration by globalization through LIBOR rates on underdeveloped countries. We’re expecting him to resume his yarn-spinning and pontification in the spring." (Published in CITY BIKE, October, 2012)

__________________

Sun Chaser, or 'Dr.G', Professor of Motorcycle Adventure at SOUND RIDER magazine. Professional Motorcycle Adventurer/Indian Motorcycle Racer/journalist/author/global economist/World's # 1 Motorcycle Adventure Sleeper & Wastrel

Soul Sensual Survivor: www.greataroundtheworldmotorcycleadventurerally.co m

Last edited by Sun Chaser; 22 Dec 2012 at 07:08.

|

27 Dec 2012

|

|

Registered Users

New on the HUBB

|

|

Join Date: Aug 2011

Posts: 16

|

|

|

clancy ride route

Hi Greg

Wondering if you have fixed a route yet.I live in on Vancouver island Canada

and would like to join up in Oregon Or???

Barry

|

27 Dec 2012

|

|

HU Sponsor

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Sep 1999

Location: Yellowtail, Montana USA

Posts: 297

|

|

|

Routes dates and locations coming

Barry:

June 2 Depart San Francisco, CA

June 2 Arrive Sacramento, CA

June 3 Depart Sacramento, CA

June 3 Arrive Medford OR

June 4 Depart Medford, OR

June 4 Arrive Portland, OR

June 5 Depart Portland, OR

June 5 Arrive Spokane, WA

June 6 Depart Spokane, WA

June 6 Arrive Butte, MT

June 7 Depart Butte, MT

June 7 Arrive Billings, MT

June 8 "Rest Day" Billings, MT

.

.

.

.

Arrive June 21, New York City

More details TBA shortly. My sabbatical detailed above and listless life as an avid motorized two wheel wandering wastrel you'll have to attribute to the void from June 8-21.

__________________

Sun Chaser, or 'Dr.G', Professor of Motorcycle Adventure at SOUND RIDER magazine. Professional Motorcycle Adventurer/Indian Motorcycle Racer/journalist/author/global economist/World's # 1 Motorcycle Adventure Sleeper & Wastrel

Soul Sensual Survivor: www.greataroundtheworldmotorcycleadventurerally.co m

|

28 Dec 2012

|

|

HU Sponsor

Veteran HUBBer

|

|

Join Date: Sep 1999

Location: Yellowtail, Montana USA

Posts: 297

|

|

|

Hendersons Across USA

While scouting the route for the USA leg of The Clancy Centenary Ride across Montana I was nearly run over by Indians....Indian Motocycles. They were on a group ride across the USA that included numerous Henderson Motorcycles.

The photo below is of a 1925 Henderson that earlier in the year had scored 99.5 points in a judging contest. The owner later experienced a front tire blow out at speed (45 mph) and went down. He offered me to "take it for a spin," figuring it was no longer 99.5 points and I would not hurt it. For the whole story on the event you can read my view here at Cannonball Endurance Run: Paying Homage to Antique Iron | Accelerate Online - Official Publication of Riders of Kawasaki

__________________

Sun Chaser, or 'Dr.G', Professor of Motorcycle Adventure at SOUND RIDER magazine. Professional Motorcycle Adventurer/Indian Motorcycle Racer/journalist/author/global economist/World's # 1 Motorcycle Adventure Sleeper & Wastrel

Soul Sensual Survivor: www.greataroundtheworldmotorcycleadventurerally.co m

|

|

Currently Active Users Viewing This Thread: 3 (0 Registered Users and/or Members and 3 guests)

|

|

|

Posting Rules

Posting Rules

|

You may not post new threads

You may not post replies

You may not post attachments

You may not edit your posts

HTML code is Off

|

|

|

|

Check the RAW segments; Grant, your HU host is on every month!

Episodes below to listen to while you, err, pretend to do something or other...

2020 Edition of Chris Scott's Adventure Motorcycling Handbook.

"Ultimate global guide for red-blooded bikers planning overseas exploration. Covers choice & preparation of best bike, shipping overseas, baggage design, riding techniques, travel health, visas, documentation, safety and useful addresses." Recommended. (Grant)

Led by special operations veterans, Stanford Medicine affiliated physicians, paramedics and other travel experts, Ripcord is perfect for adventure seekers, climbers, skiers, sports enthusiasts, hunters, international travelers, humanitarian efforts, expeditions and more.

Ripcord Rescue Travel Insurance™ combines into a single integrated program the best evacuation and rescue with the premier travel insurance coverages designed for adventurers and travel is covered on motorcycles of all sizes.

(ONLY US RESIDENTS and currently has a limit of 60 days.)

Ripcord Evacuation Insurance is available for ALL nationalities.

What others say about HU...

"This site is the BIBLE for international bike travelers." Greg, Australia

"Thank you! The web site, The travels, The insight, The inspiration, Everything, just thanks." Colin, UK

"My friend and I are planning a trip from Singapore to England... We found (the HU) site invaluable as an aid to planning and have based a lot of our purchases (bikes, riding gear, etc.) on what we have learned from this site." Phil, Australia

"I for one always had an adventurous spirit, but you and Susan lit the fire for my trip and I'll be forever grateful for what you two do to inspire others to just do it." Brent, USA

"Your website is a mecca of valuable information and the (video) series is informative, entertaining, and inspiring!" Jennifer, Canada

"Your worldwide organisation and events are the Go To places to for all serious touring and aspiring touring bikers." Trevor, South Africa

"This is the answer to all my questions." Haydn, Australia

"Keep going the excellent work you are doing for Horizons Unlimited - I love it!" Thomas, Germany

Lots more comments here!

Every book a diary

Every chapter a day

Every day a journey

Refreshingly honest and compelling tales: the hights and lows of a life on the road. Solo, unsupported, budget journeys of discovery.

Authentic, engaging and evocative travel memoirs, overland, around the world and through life.

All 8 books available from the author or as eBooks and audio books

Back Road Map Books and Backroad GPS Maps for all of Canada - a must have!

New to Horizons Unlimited?

New to motorcycle travelling? New to the HU site? Confused? Too many options? It's really very simple - just 4 easy steps!

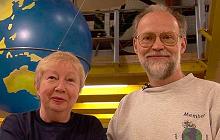

Horizons Unlimited was founded in 1997 by Grant and Susan Johnson following their journey around the world on a BMW R80G/S.

Read more about Grant & Susan's story

Read more about Grant & Susan's story

Membership - help keep us going!

Horizons Unlimited is not a big multi-national company, just two people who love motorcycle travel and have grown what started as a hobby in 1997 into a full time job (usually 8-10 hours per day and 7 days a week) and a labour of love. To keep it going and a roof over our heads, we run events all over the world with the help of volunteers; we sell inspirational and informative DVDs; we have a few selected advertisers; and we make a small amount from memberships.

You don't have to be a Member to come to an HU meeting, access the website, or ask questions on the HUBB. What you get for your membership contribution is our sincere gratitude, good karma and knowing that you're helping to keep the motorcycle travel dream alive. Contributing Members and Gold Members do get additional features on the HUBB. Here's a list of all the Member benefits on the HUBB.

|

|

|